Resources

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this podcast.

Transcript

Ray Notgrass: On today’s Exploring History podcast, we'll examine a confrontation early in the battle for civil rights for all Americans, a confrontation that occurred before the Civil War.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

In the time when some Americans owned enslaved persons, just about all black Americans, even those who were not enslaved, faced prejudice and discrimination. This was not true only in the South. Today we will look at an event that took place in New York City in 1854.

In that large city with people of many nationalities, the white population treated black persons as second-class citizens. Although slavery ended in the state of New York in 1827, almost thirty years later neighborhoods were segregated, and black persons were not allowed in many schools, churches, and restaurants. Some of the horse-drawn streetcars of that day did not permit any black riders, while other streetcar companies allowed black persons to ride only on designated cars and only at certain times.

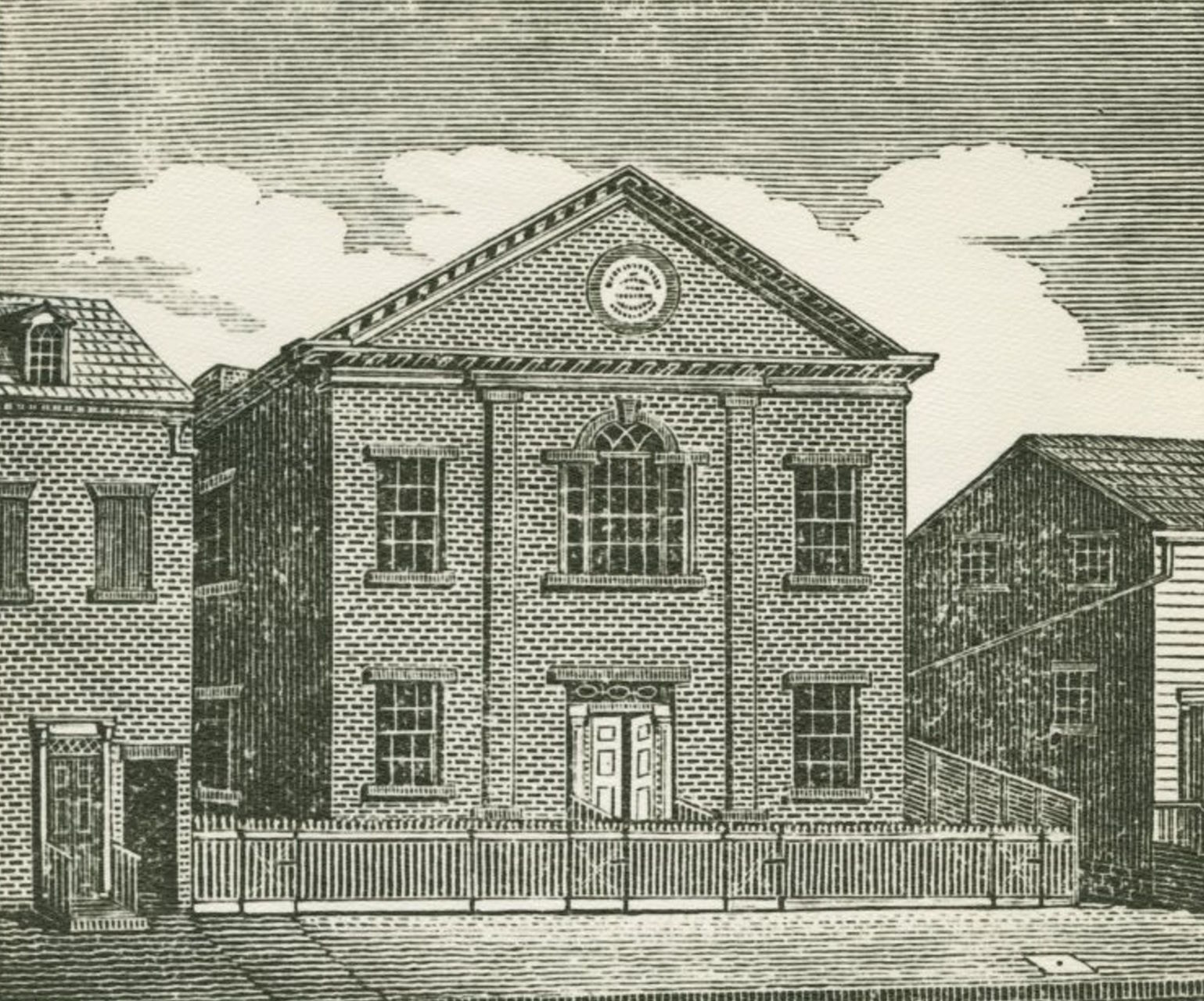

Elizabeth Jennings, who was 27 years old, was a teacher at the private African Free School and the organist at what was called the First Colored Congregational Church. Her grandfather had been a soldier in the Revolutionary War. Her father held a patent for a particular method for cleaning clothes and was a leader in the black community. Clearly, the family were responsible citizens and did not fit the stereotype that many white persons held about black persons.

On Sunday morning, July 16, 1854, Elizabeth and a friend waited on a corner for a streetcar. When one appeared, Elizabeth raised her hand to signal the driver to stop. The car did not have a placard that said “Colored Persons Allowed,” but the women were running late for church and did not have time to wait for one that did have such a sign. The driver pulled over for the women to board, but the conductor blocked their way, telling them that the car was full and that they would have to wait for a car that would take, quote, "their people," as he put it. Elizabeth replied that she was late for church and didn’t want to wait.

They had a standoff for a few minutes, then the conductor relented, saying, “You may go in, but if any passengers raise any objections, you shall go out.” This led to another exchange, whereupon the conductor grabbed her to force her off the car, but she took hold of a window sash and stayed on. The conductor called to the driver to help him, and they both took hold of her, then the driver returned to the reins. He drove until they saw a police officer, who ordered Elizabeth off the car.

Miss Jennings wrote up an account of the incident, which was read to a meeting of black citizens and published by the abolitionist Horace Greeley and in a paper that Frederick Douglass edited. Jennings filed a lawsuit against the conductor, the driver, and the streetcar company, asking for $500 in damages. Elizabeth’s father hired a white law firm to represent Elizabeth.

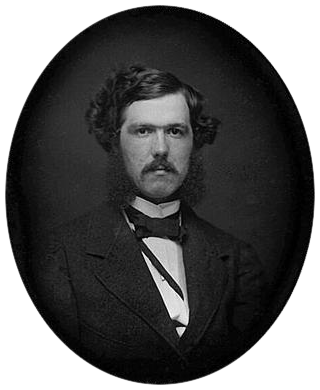

The senior partners in the law firm assigned the case to a junior partner, 24-year-old Chester Arthur, who one day would be president of the United States. In his defense, Arthur pointed out state law that held companies responsible for their employees’ actions. The judge instructed the jury that common carriers were bound to carry any respectable person, as he said, quote, “even colored persons.” The jury awarded Jennings $225, and the court added $25 plus costs.

Horace Greeley praised the decision as a warning to public transport companies, as he put it, quote, “as to the rights of respectable colored people.” The court victory did not immediately desegregate New York City streetcars, but it started the process for it. For years afterward, the organization called the Colored People’s Legal Rights Association celebrated the anniversary of the verdict.

You might wonder why we need to tell such stories as these in a time when relations among people in our country are so much better than they were in 1854. We tell them because we need to know our history, both the good and the bad. We cannot effectively navigate the present and the future unless we understand the past and how we got to where we are. We need to understand where we have come from and the victories that courageous people have won in the name of freedom and equality, and what is possible when people stand up for principle.

We also need to understand the past because of the ideas at work in such incidents as we have described today. Prejudice rises so easily against people who are different from us. It is easy to make certain groups the scapegoats for the problems we face. In years past, Americans have blamed the Irish, the Italians, and the Chinese. In Germany after World War One, people blamed the Jews for their problems. The same prejudicial thinking shows up today, when people blame the rich, or immigrants, or, as I have seen in one comment recently, and I quote, "college-educated white women," a comment made by a white man and one of the most ridiculous and prejudiced statements I have ever seen. It is easy but it is terribly wrong to blame an entire group of people for our problems. Elizabeth Jennings and her family were obviously not to blame for whatever problems existed in American society at the time, but they got unfairly blamed because they were part of a group that many people viewed with suspicion. All this makes about as much sense as emperor Nero blaming the fire in the city of Rome on Christians. The Christians were simply a handy scapegoat when Nero needed to divert the blame to someone. This kind of prejudiced blaming is not the way to treat people nor is it the way to address our problems constructively, primarily because it is not true. Such thinking divides people and does not bring people together.

Of course, not everyone who held prejudice against black persons in the 1800s was what we would call a bad person. Many were good people who let themselves be influenced by the tenor of the times or perhaps were afraid to take a stand against the mistaken majority of the day. That same kind of failing is quite possible today in any of us. This is why we must put Christ first in our hearts and minds and let the One who reached out to Samaritans and other outcasts of the day guide our thinking and our actions.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this episode.