Resources

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this podcast.

Transcript and Photos

Ray Notgrass: On today's Exploring History podcast, I'll tell about the courage and conviction that a group of teenagers demonstrated. I'll talk about the Little Rock Nine.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: When Central High School was constructed in Little Rock, the capital of Arkansas, in 1927, the American Institute of Architects named it the most beautiful high school in America. It is a huge and impressive building. We have visited there. Little Rock Central was constructed for white high school students. Thirty years after it opened, the Little Rock School Board prepared to admit the school's first African American students. Nine brave teenagers prayed and prepared to be those students.

In 1896, the United States Supreme Court had ruled that states could require black and white citizens to use segregated public facilities as long as the facilities for each were equal. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court announced a landmark decision in the case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The justices declared that having separate public schools was illegal according to the U.S. Constitution. The following year, the Supreme Court declared that schools must be integrated "with all deliberate speed."

The Little Rock School Board decided to integrate gradually, starting with Little Rock Central High School. Central had more courses and more extracurricular activities than the high school where African American students attended. Hundreds of students volunteered to be the first African Americans to integrate Central. Civil rights leaders from the NAACP, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, chose 10 of them. Each was an excellent student and each was committed to participating in this historic event. Leaders met with them, prayed with them, and helped them prepare for what might happen. One student later decided not to participate. The remaining students became known as the Little Rock Nine.

In late August, a group of white women formed the Mothers League of Central High School. The Mothers asked Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus to prevent the integration of the school. On Labor Day, September 2, 1957, the governor gave a speech on television stating that he was going to send the Arkansas National Guard to Central High to prevent the violence he expected would happen when African American students entered the school. On September 3rd, the Arkansas National Guard allowed white students and teachers to enter Central High, but they prevented African American support staff members from entering. But they prevented African American support staff members from entering. No African American students tried to enter that day.

On September 4th, the Little Rock Nine arrived at the high school. They were Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershead, Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, and Carlotta Walls. An angry, shouting, rock-throwing mob terrorized the students. The mob and the Arkansas National Guard prevented them from entering. President Eisenhower sent Governor Faubus a telegram telling him that he would make sure the Constitution was upheld by every legal means he could use. On September 14th, Governor Faubus traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, to meet with Eisenhower, who was on vacation there. The NAACP went to court to prevent Governor Faubus from blocking the teenagers’ entry into the school. On September 20th, a federal judge ruled in favor of the students.

On September 23rd, Little Rock police escorted the Little Rock Nine into Central High School amidst a thousand angry white protesters. The police later had to escort the African American students out of the back of the school because of fear for their safety. President Eisenhower called the actions of the rioters disgraceful.

On September 24th, the president sent 1,200 members of the U.S. Army's 101st Airborne Division from Fort Campbell, Kentucky, to keep peace in Little Rock. Eisenhower placed the Arkansas National Guard under the authority of the federal government instead of Governor Faubus. That night Eisenhower gave a speech to the nation on television about the situation in Little Rock.

On September 25th, U.S. Army General Edwin Walker spoke to the white students in the school auditorium. Then the nine African American students entered the building with an army escort. This time the Little Rock Nine were able to stay the whole day. Soldiers guarded them as they went to their classes.

For the first month, army vehicles took the students to school each day. Finally, on October 25th, they went to school in civilian cars. Guardsmen gradually took over the duties of the 101st Airborne. By the end of November the last of the 101st Airborne soldiers left Little Rock.

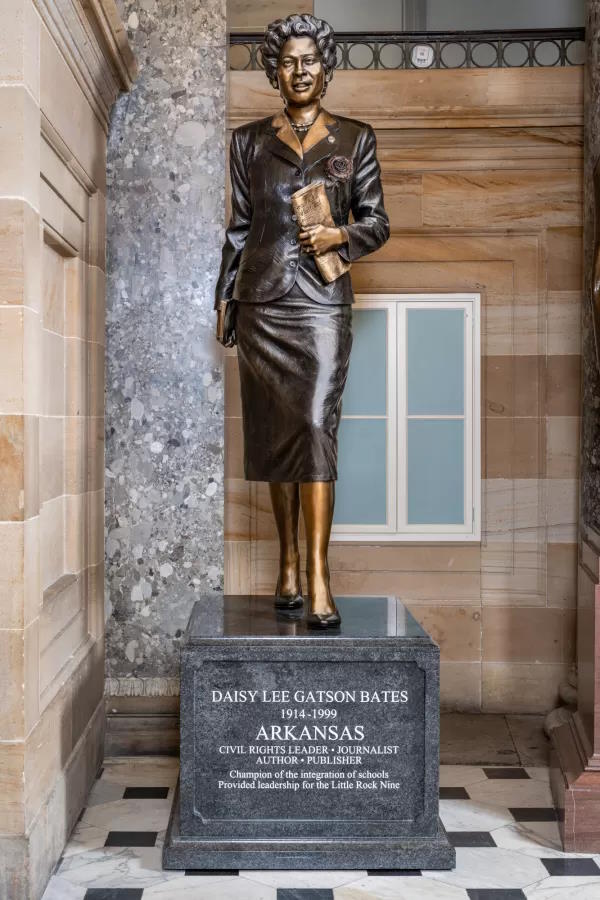

Daisy Bates was an African American leader in Little Rock. She was the president of the Arkansas chapter of the NAACP. Her husband was the publisher of Little Rock's largest African American-owned newspaper. She was his star reporter. Mrs Bates became a personal friend and mentor to the Little Rock Nine. She was influential throughout the integration process. During the crisis she said, "Any time it takes 11,500 soldiers to assure nine Negro children their constitutional rights in a democratic society, I can't be happy."

The African American students continued in school, but some white students attacked them verbally and physically. About 100 white students were suspended for a few days that year. Four were expelled from school entirely. After months of students being mean to her. Minnijean Brown yelled back when some white girls said mean things to her and one of them hit her on the head with a purse. The principal expelled Minnijean. An African American family invited her to live with them in New York. She graduated from high school there.

In May of 1958, Ernest Green, the only senior among the Little Rock Nine, became the first African American to graduate from Little Rock Central High School. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. attended the ceremony. In June, a union of hotel workers in New York City brought the Little Rock Nine to New York and gave them an award for improving race relations. The teenagers went to a Broadway musical, toured the UN headquarters, and visited the Statue of Liberty. They met Mayor Robert Wagner of New York City and UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld.

A few days after graduation, the Little Rock School Board began an effort to get the courts to allow them to delay the integration of their schools. On September 12, 1958, the Justices of the Supreme Court ordered the Little Rock School Board to open integrated schools on September 15. Governor Faubus ordered all Little Rock high schools to close until citizens could vote on the issue.

On September 27th, citizens voted 19,470 against integration and 7,561 for it. The high schools were closed for the entire school year. Both white and African American students watched classes on television. Instead of being able to choose from the 87 subjects they would have had at school, they were only able to take English, history, math, and science. A group of women formed the Women's Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools. The schools reopened in August of 1959.

Congress passed and President Eisenhower signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and the Civil Rights Act of 1960, though many Democrats and Republicans opposed them. These were our nation's first national civil rights laws since Reconstruction. They increased the civil rights of African Americans. In Eisenhower's televised speech we mentioned earlier, he said:

To all the peoples of the world, I once more give expression to America's prayerful and continuing aspiration. We pray that peoples of all faiths, all races, all nations may have their great human needs satisfied, that those now denied opportunity shall come to enjoy it to the full and that, in the goodness of time, all people will come to live together in a peace guaranteed by the binding force of mutual respect and love.

The integration of Little Rock Central High School was a milestone in the history of the Civil Rights Movement, which is the history of Americans learning to live, work, and learn together. The Ernest Green Story is a 1993 made-for-television movie that is a dramatization but a good presentation of the story of the Little Rock Nine. Some of the students have written books about their experience.

All of the nine students went on to successful careers in various fields. In 1977, Little Rock Central High School was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It became a National Historic Site in 1998. In 1999 each of the Little Rock Nine received the Congressional Gold Medal. In 2005 the Little Rock Nine Memorial was dedicated on the grounds of the Arkansas State Capitol. The memorial has statues of each of the nine students and they are walking holding books, and they are facing the governor's office in the state capitol. Earlier this year, the state of Arkansas placed a statue of Daisy Bates in the statuary hall of the U.S. Capitol.

Of the nine students, seven are still living, all in their 80s now. Jefferson Thomas died in 2010, and Thelma Mothershed Wair died in October of this year. The monument on the grounds of the Arkansas State Capitol includes quotes from each one of the students.

Jefferson Thomas said, "As a youth, God blessed me with the courage of men. As a man, he gave me the spirit of youth."

Carlotta Walls Lanier said, "Hard work, determination, persistence, and faith in God were lessons learned from my parents, Cartelou and Juanita Walls. I was only doing what was right."

Melba Pattillo Beals said, "The task that remains is to embrace our interdependence, to see ourselves reflected in every other human being and to respect and honor differences."

Thelma Mothershed Wair said, "To God be the glory."

This podcast was drawn largely from a lesson in America the Beautiful, a curriculum written by Charlene Notgrass and published by Notgrass History. I'm Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this episode.