Resources

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this podcast.

Transcript

Ray Notgrass: On today’s Exploring History podcast, I’ll tell how a few letters from a single woman helped change a president and change the course of American history.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

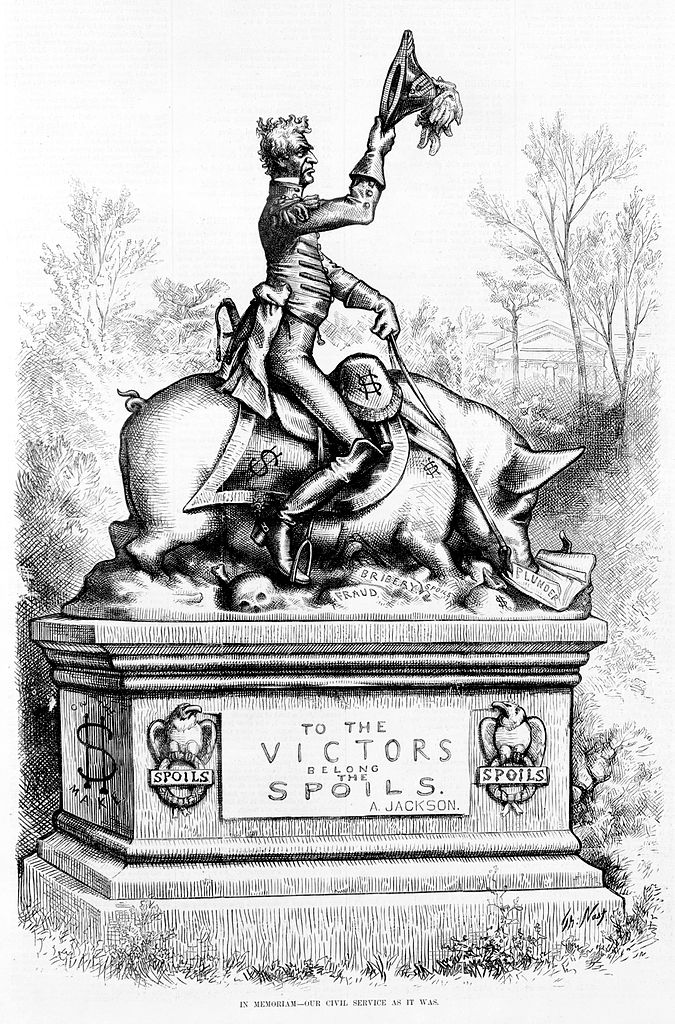

Ray Notgrass: In the last half of the 1800s, politics in America was particularly dirty. Political machines ran many of the big cities, and people in power gave out government jobs as favors rather than giving them to qualified applicants. It was hardly government of the people, by the people, and for the people. Instead, it was more a matter of let’s see how much we can steal for ourselves at the public trough.

The Democratic party was definitely the weaker of the two parties. Their strength lay largely in the South, the former Confederate states, and only because they denied African Americans the right to vote. Voters did not elect a Democrat as president from 1856, when Democrat James Buchanan was elected, until 1884, with the election of Democrat Grover Cleveland--a period of 28 years. The representation of the parties in Congress during this time was not as one-sided as that, but the Democrats were clearly the minority party.

Since the Republican party was so dominant, of course they had a split within the party between two different factions. One group was called the Stalwarts and they wanted things to stay the way they had been. Machine politics had kept them in power, so they saw no need for change. Giving out government jobs to the party faithful seemed to be just the way to do business, so they saw no need to change. And party officials made it clear to government employees that they were expected to contribute to the party to finance the next election.

The other faction in the Republican party was the Reformers. This group saw the need for reforms in government and thought the Republican party should lead the way in making these reforms. For instance, they wanted to end the practice of pressuring government employees to make financial contributions to political parties. They wanted what was called civil service reform in how people were hired for government jobs. They believed that competitive exams were the best way to identify people who were qualified to fill the jobs that were supposed to serve the public and not just be plums handed out to party supporters. Since the Reformers held to some Republican principles but worked against other traditional Republican positions, their critics called them Mugwumps, because, the critics said, they had their mugs on one side of the political fence and their wumps on the other side. Another term that some used to describe the reformers was Half-Breeds–half Republican and half not. Within the Republican party, the Stalwarts were the majority while the Reformers were the minority, but the latter grew in strength as the 1800s unfolded.

As the 1880 presidential election approached, several Republicans expressed interest in obtaining the party’s presidential nomination. This was the time when a party’s national convention actually chose the party’s nominee. The few state primaries that existed played little to no role in the process. Each state’s party machinery selected that state’s delegates to the convention, and whichever faction–Stalwarts or Reformers– controlled that state’s party machinery decided who would be the delegates. Delegates often had to pledge to support one candidate at least for the first ballot. The taking of more than one ballot was common in those days. State and national party leaders met in the traditional smoke-filled hotel rooms making deals to help their preferred candidates. Negotiations included such deals as, “If you’ll support our man, we’ll see that Congress passes a certain law that you want” or “We’ll support your man for president if you will support our man for the vice-presidential nomination” and that kind of back-and-forth bargaining.

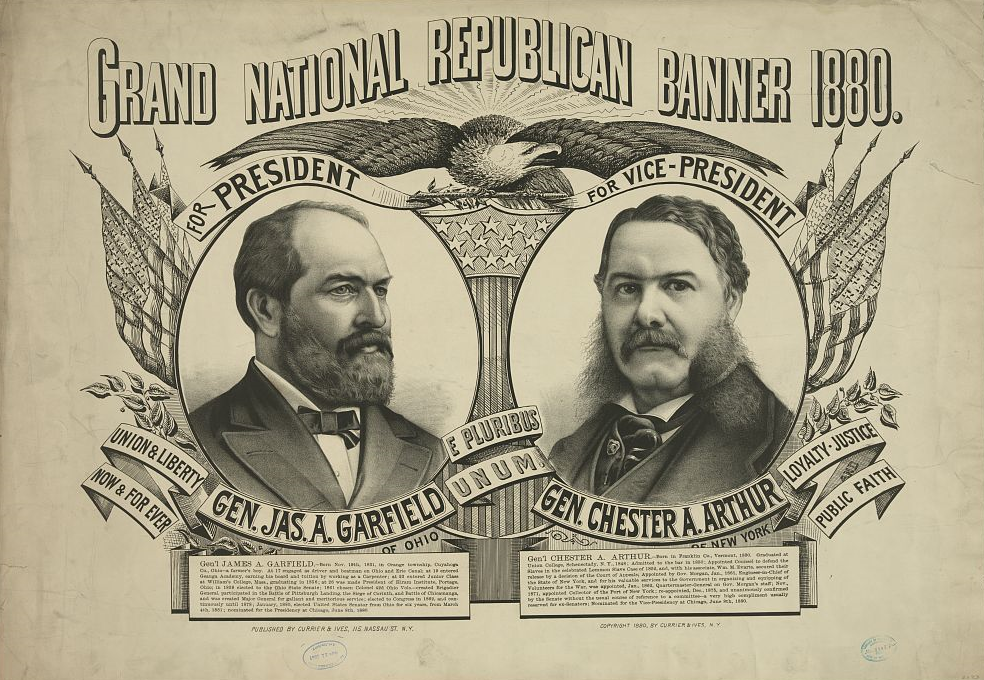

After several ballots in which no candidate generated decisive interest, a delegate put forward the name of James Garfield as a possible choice. Garfield was from Ohio, a key state for the Republicans to carry. He was born in a log cabin, had taught at a college, studied law, and served as a minister and later an elder in the Disciples of Christ. Garfield served with distinction in the Union army during the Civil War. He served several terms in the U.S. House of Representatives, and earlier in 1880 the Ohio legislature had chosen him to be a U.S. senator. Garfield was well-liked and an effective speaker. He was not really interested in the Republican presidential nomination in 1880, but when the convention turned to him on the 36th ballot, he accepted.

Garfield was a Reformer, so the Stalwarts wanted one of their men to fill the second spot on the ticket. New York was a state that the Republicans had to carry to win the election. After much backroom negotiating, the nod for the vice-presidential nomination went to Chester Arthur of New York City.

Chester Arthur? Nobody, especially Arthur himself, expected ever to see him on a national ticket. Chester Arthur was the model machine politician. He loved giving elaborate parties for his friends. He was adept at handing out jobs and other favors to help his fellow Republicans. For several years, he ran the Customs House of the Port of New York, and it was well known that his dealings in that office were not always on the square. But the convention delegates knew they had to carry New York state, so they gave in to Stalwart pressure and nominated Arthur for vice president, knowing that much of the country would have low expectations for him.

The Garfield and Arthur ticket won the election, and the next year, after they were sworn into office, Garfield began assembling his administration, including fellow Reformers among his appointees. Then the unthinkable happened. On July 2, 1881, a disappointed and deranged office seeker, Charles Guiteau, shot Garfield in the back as the president walked through a Washington train station. As Guiteau peaceably surrendered to police, he proclaimed, “I am a Stalwart. Arthur is president now.”

Garfield lingered on until September 19, when he passed away. Arthur, who was out of town at the time of the assassination, did not want to return to Washington immediately for fear of looking too eager to assume the presidency. Arthur did not aspire to the presidency. In fact, the thought of becoming president filled him with dread. Nevertheless, some people suspected him as being behind the assassination attempt so he could put the Stalwarts back in charge.

During the time that Garfield lay dying, Chester Arthur received a seven page handwritten letter from Julia Sand of New York City. Sand was 31 years old, single, well educated and intelligent, and an invalid due to several ailments but interested in politics. She was the daughter of a German immigrant who had achieved a measure of financial success. Sand and Arthur did not know each other. Her letter was amazing in its forthrightness and in its call for Arthur to rise above his checkered past and the low expectations that people had of him and to be a president of honor that the nation could respect. I quote from the letter:

The hours of Garfield’s life are numbered - before this meets your eye, you may be President. The people are bowed in grief; but - do you realize it? - not so much because he is dying, as because you are his successor. What President ever entered office under circumstances so sad! The day he was shot, the thought rose in a thousand minds that you might be the instigator of the foul act. Is not that a humiliation which cuts deeper than any bullet can pierce? Your best friends said: “Arthur must resign - he cannot accept office, with such a suspicion resting upon him.” And now your kindest opponents say: “Arthur will try to do right” - adding gloomily - “He won’t succeed, though - making a man President cannot change him.” But making a man President can change him! At a time like this, if anything can, that can. Great emergencies awaken generous traits which have lain dormant half a life. If there is a spark of true nobility in you, now is the occasion to let it shine. Faith in your better nature forces me to write to you - but not to beg you to resign. Do what is more difficult & more brave. Reform! It is not the proof of highest goodness never to have done wrong - but it is a proof of it, sometime in one's career, to pause & ponder, to recognize the evil, to turn resolutely against it & devote the remainder of our life to that only which is pure & exalted. Such resolutions of the soul are not common. No step towards them is easy. In the humdrum drift of daily life, they are impossible. But once in a while there comes a crisis which renders miracles feasible. The great tidal wave of sorrow which has rolled over the country, has swept you loose from your old moorings & set you on a mountain top, alone. As President of the United States - made such by no election, but by a national calamity - you have no old associations, no personal friends, no political ties, you have only your duty to the people at large. You are free - free to be as able & as honorable as any man who ever filled the presidential chair. Your past - you know best what it has been. You have lived for worldly things.. fairly or unfairly, you have won them. You are rich, powerful - tomorrow, perhaps you will be President. And what is it all worth? Are you peaceful - are you happy? Rise to the emergency. Disappoint our fears. Force the nation to have faith in you. Show from the first that you have none but the purest aims. It may be difficult to inspire confidence, but persevere. In time - when you have given reason for it - the country will love & trust you. If any man says: “With Arthur for President, Civil Service Reform is doomed,” prove that Arthur can be its finest champion. Appoint those only of marked ability & of sterling character. Such may not be abundant, but you will find them if you seek them. Your name now is on the annals of history. You cannot slink back into obscurity, if you would. A hundred years hence, school boys will recite your name in the list of presidents & tell of your administration. And what shall posterity say? It is for you to choose whether your record shall be written in black or in gold. For the sake of your country, for your own sake & for the sakes of all who have ever loved you, let it be pure & bright. As one of the people over whom you are to be President, I make you this appeal.

Julia Sand went on to write a total of 23 letters to Chester Arthur. She gave advice on political matters. She described her personal situation. She asked–more than once–for him to come see her. Arthur paid her one visit, on August 20, 1882. He stayed for about an hour. Her family was present, so they did not have the deep political discussion she had hoped for. But he came. As far as we know, he never replied to any of her letters.

We don’t know how much Julia Sand’s letters influenced Chester Arthur as president, but we do know that he kept her letters and that he did not live down to the low expectations that many people had of him. At one point early in his presidency, Stalwart leader Roscoe Conkling criticized Arthur publicly. Conkling had engineered Arthur’s nomination for the vice presidency. Arthur responded to Conkling’s words by saying, “For the vice presidency I was indebted to Mr. Conkling. But for the presidency of the United States my debt is to the Almighty.”

Arthur vetoed the first Chinese Exclusion Act, which limited the right of Chinese citizens to immigrate to the United States, although he later signed a revised version. He vetoed a pork-barrel laden bill that would have spread the public’s money to many projects that could win votes, although Congress overrode his veto.

Arthur urged Congress to ban enforced political contributions by public employees, which was a major break with the Stalwarts. He wanted to see legislation to preserve forests on public land instead of letting private companies come in and destroy those forests. He reached out to African Americans on numerous occasions and urged Congress to pass new civil rights legislation.

Sand complimented Arthur on the dignified way that he conducted himself during Garfield’s slow decline. She complimented his taste and tact after a speech he gave. And even though Arthur was a Stalwart, he supported civil service reform, and signed the bill that Congress sent to him that started the movement away from political appointments and toward merit-based appointments to government positions.

Arthur did not actively pursue renomination in 1884. He rejected efforts on his behalf to win the nomination. Unknown to the public, Arthur was dying of Bright’s disease, an inflammation of blood vessels in the kidneys. He died on November 18, 1886, at the age of 57. During his presidency and after his death, Arthur’s administration received wide praise from the American public.

Julia Sand was placed in an institution in 1886 for mental problems, and remained there until her death in 1933 at the age of 85.

Can one person make a difference? He or she certainly can, as history tells us over and over. We all have many pressures and many people who would influence us for good or ill. We have to devote ourselves to the good and demonstrate, in Lincoln’s phrase, the better angels of our nature. Julia Sand used what influence she had to turn Chester Arthur to better ways. Our country benefitted from that.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening. And think about writing a letter that just might change history.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this episode.