Resources

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this podcast.

Transcript

Ray Notgrass: On today’s Exploring History podcast, we’ll look at what some people called the Trial of the Century, the trial that helped to define the modern conservative movement. We’ll examine the perjury trial of Alger Hiss.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: Seventy-five years ago, a court trial in America gripped the nation. This trial defined in stark terms the dramatic political conflict that was enveloping the world. The trial helped to define political conservatism in America for the last half of the 20th century to today. I’m talking about the perjury trial of American diplomat Alger Hiss. His accuser, Whittaker Chambers, claimed that Hiss was a Communist in the active service of the Soviet Union while he served in the U.S. government.

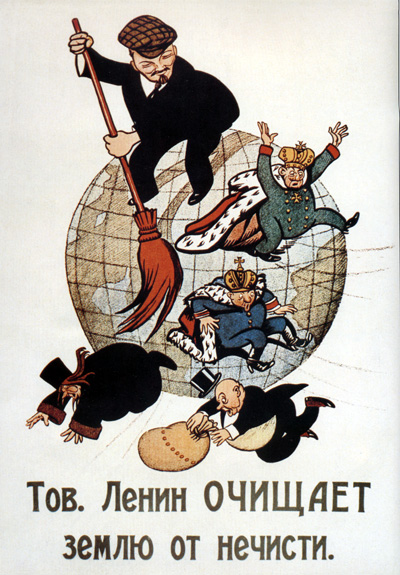

In post-World War II America, Communists were everywhere–at least, that is what some people thought. The Communist philosophy had been around since the mid-1800s, but it had burst upon the world scene with the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia in 1917. Communists promised to free the workers of the world from the oppression of the ruling class and usher in a workers’ paradise in which everyone would contribute what they could and everyone would receive just what they needed. This revolution installed a Communist government in Russia which then conquered smaller countries around Russia, thus forming the Soviet Union. Communists minced no words when they stated their goal of world revolution. They intended to install Communist governments around the world.

During World War II, the United States and Great Britain had an uneasy alliance with the Soviet Union against Germany. The Soviets were not fighting for freedom. The Soviets were fighting against the threat of German aggression. But as the war progressed and Hitler’s Germany fell, the Soviet Union installed puppet Communist governments in several Eastern European countries, governments that answered to the Soviet leaders in Moscow.

Many people in the United States knew that Communists had their eyes on taking over other countries in Europe and taking over the United States. Communist political parties in some western European countries had sizable support from the people, who were tired of conflict after two world wars and who struggled to maintain a decent standard of living on their war-torn continent. Communists were not as numerous or as influential in the United States as they were in Europe, but they had a very real presence in this country and many people were concerned that their influence might grow. Many Americans were concerned that Soviet spies might be infiltrating the U.S. government and obtaining secret information that they were sending to leaders in the Soviet Union. Occasional investigations would uncover spies working in the United States, so the threat was real.

The U.S. House of Representatives formed a Committee on Un-American Activities (often abbreviated HUAC for the House Un-American Activities Committee). Its responsibility was to investigate allegations and charges involving possible Soviet espionage activities in the United States. The committee heard from various witnesses who gave their stories about knowing or suspecting Communists in the government. One name that came up in the committee’s investigations was Alger Hiss.

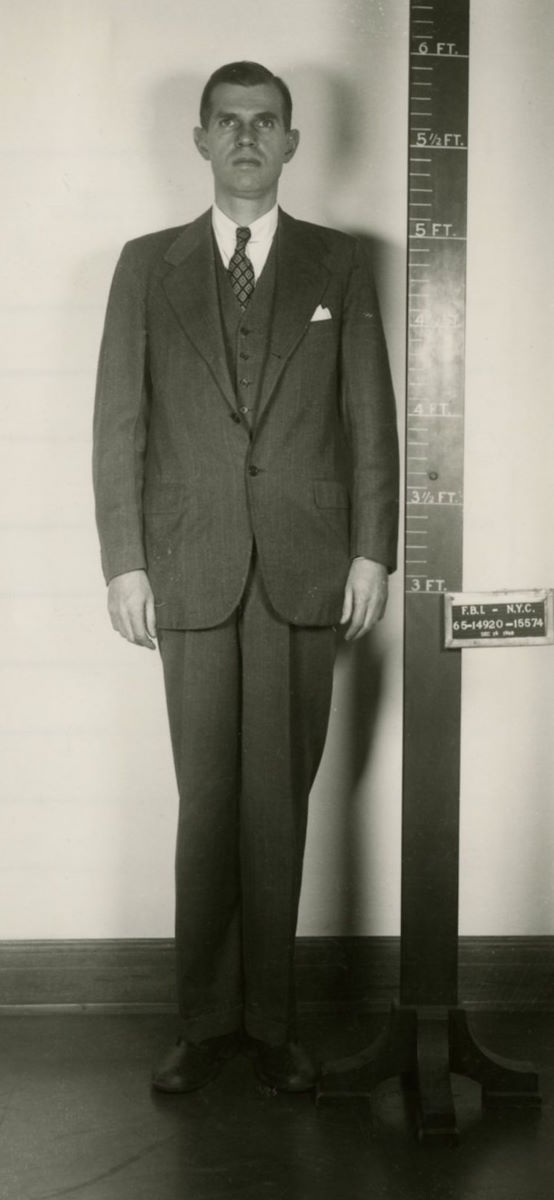

To investigate Hiss further, in 1948 the committee subpoenaed Whittaker Chambers, who at the time was a senior editor for Time magazine. Chambers told the committee that during the 1930s he was an active Communist who worked as a spy for the Soviet Union in the Communist underground in the United States and that one of his frequent contacts was Alger Hiss. At the time, Hiss had been an official in the U.S. State Department. He was later part of the U.S. delegation to the Yalta Conference near the end of World War II, he had played a role in the founding of the United Nations, and then he became president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Chambers described in detail how he and Hiss worked together to obtain official government documents and forward them to Moscow. Chambers and his wife and Hiss and his wife had been good friends, and they had spent considerable time with each other socially.

Chambers’ allegations against Hiss were a bombshell. Hiss was widely respected in high levels of American government. He was socially prominent and always impeccably dressed. Many prominent people in the Washington establishment stood up for Hiss and said they could not imagine him being a Communist. Chambers, on the other hand, was overweight and dressed somewhat carelessly. Socially speaking, Chambers was a nobody. It seemed that Chambers’ accusations were made-up stories that were hardly believable. During the committee’s hearings, Hiss at one point looked Chambers full in the face and said he wasn’t sure he had ever seen him before, although he later admitted having known him.

Hiss categorically denied Chambers’ allegations and he sued Chambers for libel. The case caused a national controversy. Who was telling the truth–Hiss or Chambers? Chambers then released another bombshell. From the pumpkin patch of his Maryland farm, Chambers produced microfilm copies of government documents that he said Hiss had given him and that only Hiss could have given him. Some of the documents had notes in Hiss’ handwriting. These were the so-called “Pumpkin Papers” that proved Chambers and Hiss had known each other during the 1930s.

Hiss was indicted for perjury, for lying under oath to a grand jury about knowing Chambers. He was not charged with espionage because the statute of limitations had expired on any possible espionage activity. However, the jury deadlocked and the judge declared a mistrial. A second trial was held, and 75 years ago, in January of 1950 a jury convicted Hiss of two charges of perjury for lying about his relationship with Chambers under oath. Hiss served two concurrent five-year prison terms, but he always denied being a Communist. Hiss died in 1996 at the age of 92, and to his dying day he denied being a Communist. In 1957 Hiss published a book in defense of his story that he titled In the Court of Public Opinion.

In 1952 Chambers published his memoir, called Witness, in which he told his life story, including his years as a Communist and his life after leaving Communism. He makes clear that he left Communism because of his newfound faith in God. Chambers died in 1961.

Chambers’ book is a large volume but it is well worth reading (an audio version is available). In the book, Chambers is frankly pessimistic about the chances for freedom and democracy triumphing over Communism. However, the fall of Communism in the late 20th century showed that a triumph over Communist oppression is possible, but the fight goes on.

The FBI conducted an investigation into Hiss and his activities and uncovered evidence pointing toward his involvement in Communist espionage. After the fall of Communism in the Soviet Union, the files of the Soviet KGB (their Secret Police) were opened to public inspection. The evidence in the files did not unquestionably confirm Hiss’ role as a Communist spy, since the records were in code; but they contained some references to people and events that pointed to Hiss and that could only be pointing to Hiss.

The Hiss case played an important role in American politics. In immediate terms, it brought to prominence a young congressman from California named Richard Nixon. Nixon was on the House Un-American Activities Committee, and he stoutly defended Chambers. Nixon became known as a strong anti-Communist, and with this case Nixon started his rise in national prominence. In 1952, Dwight Eisenhower chose Nixon to be the Republican vice presidential nominee. The rest, as they say, is history.

The Hiss case also gave the conservative movement in America a strong anti-Communist stamp. Before this, conservatives were known mostly for their opposition to Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal in domestic policy. Now conservatives had an international cause to champion, and they began giving ample warning about the dangers of Communism at home and abroad. As the years unfolded, authorities identified other Communist agents and spies within the United States. Conservatives did not have to go to the extremes and unfair tactics of Joe McCarthy to make the case that Communists were a clear and present danger in the United States, but they had a valid case to make. We have to remain watchful against the influences of Communism even today. The courage and honesty of Whittaker Chambers lit the fire of vigilance that continues to burn.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this episode.