Resources

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this podcast.

Transcript and Photos

Ray Notgrass: A world conflict with unprecedented loss of life and destruction and ending with an imperfect peace. Sound familiar? On today’s Exploring History podcast, we’ll actually be going back over one hundred years to talk about the Great War, or World War I, and its greatest hero, Alvin C. York.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: I'm Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening. People often say “war broke out” at a certain time and place, but war doesn't break out like a rash or measles. Wars are the result of a long series of problems and conflicts that often go back for years if not centuries, and that finally come to active fighting. So it was with World War I, known at the time as the Great War because they didn’t know there would be another world war in twenty years. And what was a country boy from a little community in Tennessee doing in Europe with a gun in his hands? I hope to explain all this in today’s podcast.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, several countries pursued a policy called imperialism, which means they wanted to build empires. The thinking was that having overseas colonies would build a country’s economy, wealth, and prestige. For instance, European countries controlled almost the entire continent of Africa. Great Britain held the huge subcontinent of India. The United States got into the act with the colonies it gained in the war with Spain in 1898, including Cuba and the Philippines. The race for empire brought tension and competition among empire-building countries.

A second factor increasing the possibility of war that was actually counter to the drive for empire, was the movement in several smaller countries called nationalism. Nationalism is a people group’s wanting to be rid of foreign domination and chart their own destiny. One place that had particularly strong nationalist movements was the Balkan peninsula in southeastern Europe. The Balkans, as the region was called, had several ethnic nationalities, as it still does, but the Austro-Hungarian Empire controlled it. The Serbians were one group that especially wanted to be free.

A third factor that increased the possibility of war were the alliances that several countries had with other countries, each one promising to come to the other’s aid in case they were attacked, and thus creating a stronger force to try to prevent being attacked. One of the strongest arrangements of this kind were the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Austria had taken over Hungary and imposed its own royal family on Hungary. In an attempt to limit the threat of the Central Powers, three other countries formed the Triple Entente, which is French for stopping or resistance. These countries were Great Britain, France, and Russia, which was a monarchy at the time.

Complicating the increasingly tense situation still more were the rivalries that countries had with other countries. For instance, France and Russia were both suspicious of Germany’s military buildup. Great Britain was suspicious of Germany also, and Germany was suspicious of Britain’s intentions in the world and jealous of Britain’s power in the world. Russia didn’t like Austria-Hungary’s domination of the Balkans region.

All that this kindling needed was a spark to set the world ablaze, and it happened. In June of 1914, the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, visited the city of Sarajevo in the Balkans on what was billed as a goodwill visit, but the visit also served to remind people in the Balkans who was boss. Gavrilo Prinzip was a Serbian living in Bosnia who had pledged himself to doing what he could to get rid of Austro-Hungarian control. Prinzip assassinated the archduke and his wife as they rode through the streets of Sarajevo. In response, Austria-Hungary issued a series of demands on Serbia, such as rooting out all anti-Austrian groups and stopping the publication of all anti-Austrian propaganda. The government of Serbia agreed to meet most of the demands, but most was not good enough for Austria. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and the dominoes began to fall.

Russia mobilized its military forces to help their fellow Slavs in Serbia. Germany declared war on Russia to help its ally Austria-Hungary. France declared war on Germany. Germany decided to attack France. In previous years France had built a series of fortifications on its border with Germany. To avoid this line of defense, called the Maginot Line, German forces simply went around it by moving through neutral Belgium. Great Britain had promised to protect Belgian neutrality, so Great Britain declared war on Germany. The Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria also fought on the side of the Central Powers.

Soon war engulfed all of Europe. Each side dug trenches along a 600-mile front in eastern France and started shooting at each other. Every once in a while one side or the other would attack a portion of the front, and they would either gain a few yards or miles or be driven back. Both sides suffered terrible losses. New weapons such as machine guns, poison gas, land mines, tanks, and aerial bombing made possible the relatively new invention called the airplane took a terrible toll. For instance, during the Battle of the Somme, 20,000 British soldiers were killed and 40,000 were wounded in one 24-hour period. Fighting also took place elsewhere in Europe and in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

As all of this happened, where was the United States? President Woodrow Wilson pursued a policy of strict neutrality. Most Americans favored Great Britain’s cause, but many German immigrants in the United States wanted Germany to emerge victorious. The U.S. had closer ties to Great Britain, but the idealistic Wilson believed he could avoid getting involved in the European War at all. When Wilson ran for reelection in 1916, his motto was, “He kept us out of war.”

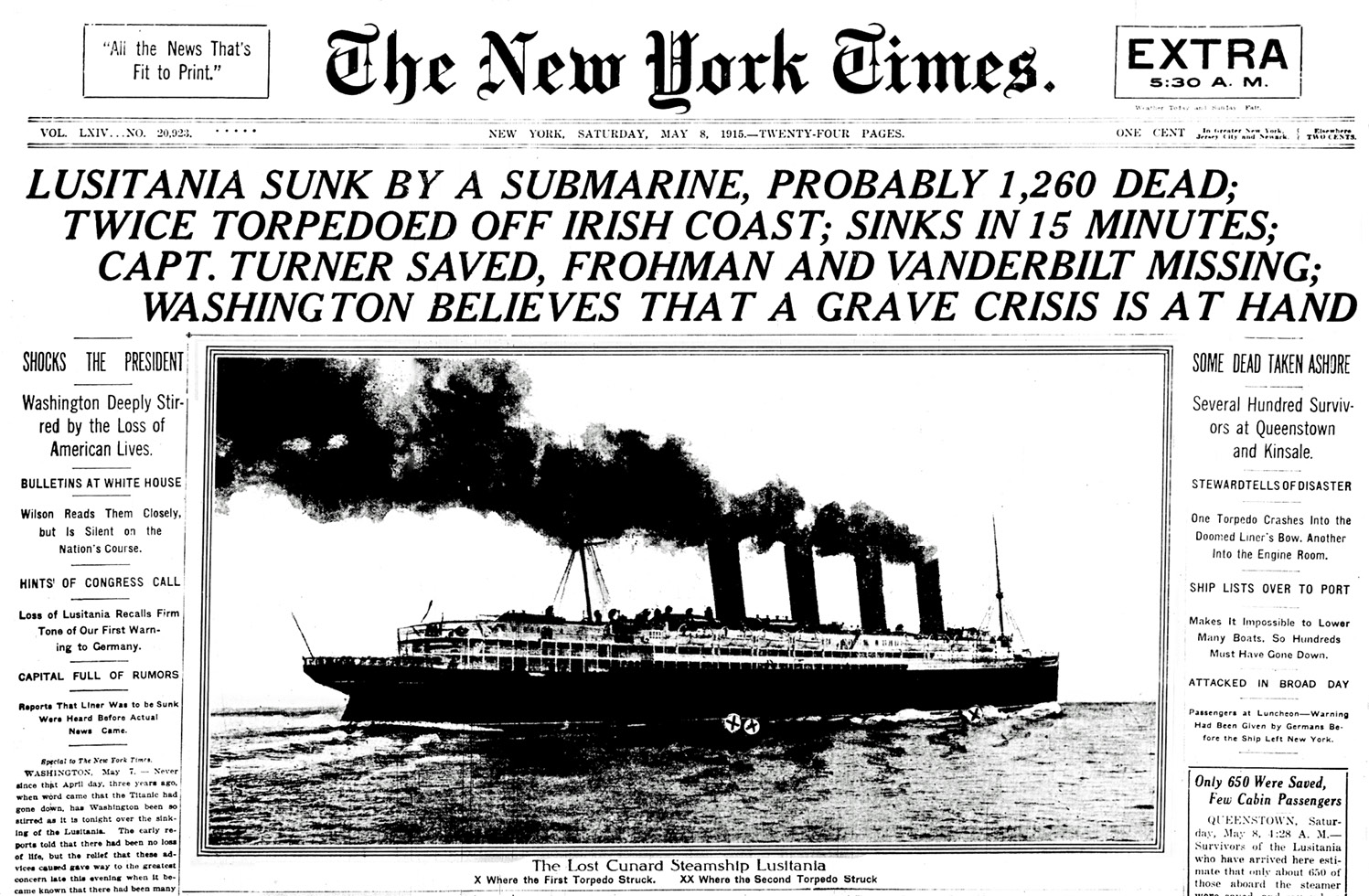

However, Germany eventually pursued a policy of unrestricted naval warfare, declaring that it would attack any ships that were aligned with one of its enemies. Anyone traveling on such a ship, Germany declared, did so at their own risk. This move violated the American policy of neutrality of the seas. Germany carried out these attacks with their submarines or U-boats (short for unterseebooten). For instance, on May 7, 1915, a German U-boat sank the British passenger liner the Lusitania, causing the loss of almost 1,200 people, including 124 Americans. Wilson still resisted calls for a declaration of war against Germany.

One final German insult of the United States came in the Zimmerman telegram. The German foreign minister Arthur Zimmerman sent a telegram to the German ambassador in Mexico City. Zimmerman wanted the German ambassador to encourage Mexico to come into the war on the side of the Central Powers. Zimmerman said that if Mexico did this and if Germany won the war, it would attempt to help Mexico, as the telegram said, “regain lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona.” British intelligence intercepted the telegram and made it public, and many Americans were outraged by what it said.

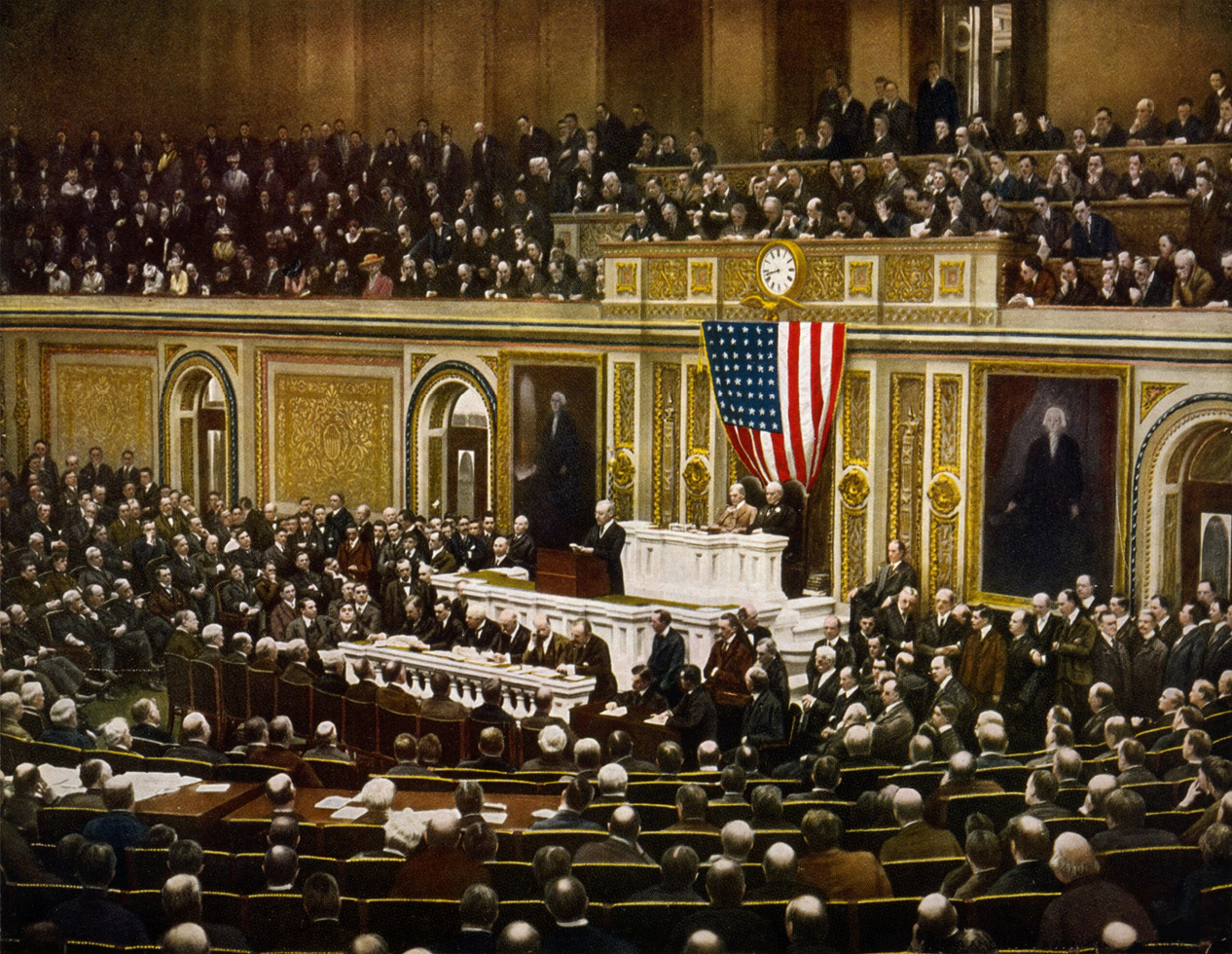

Finally on April 2, 1917, almost three years after the war began, President Wilson asked Congress to declare that a state of war existed between the United States and Germany. Congress approved a war resolution on April 6. One of about 50 members of Congress who voted against going to war was Jeanette Rankin. Rankin had been elected to the House from Montana in 1916. Rankin did not serve another term in the House until she was elected again in 1940. Then after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, she was the only member of Congress to vote against America’s entry into World War II. Rankin only served these two terms in Congress, but during these two terms she managed to vote against America entering both World War I and World War II.

The United States had to gear up for war quickly. With a small standing Army of less than 400,000 men, enlistments and the military draft built an army that eventually numbered over three and a half million personnel. With all these men being called for service, women entered the workforce in greater numbers than ever before. When the war began, hundreds of Americans who were in Europe for business or vacations were trapped and couldn’t get home. President Wilson asked a successful mining engineer named Herbert Hoover to do what he could to get these Americans out of Europe. Hoover was amazingly successful. Hoover also led a food drive to feed Belgians who had lost their usual sources of food because of the war.

Back home Hoover also led drives in the U.S. to help the war effort, such as encouraging Meatless Tuesdays and Wheatless Wednesdays to make sure that the troops had the food that they needed. Wartime led to the start of widespread Daylight Saving Time in an attempt to use daylight more efficiently.

The war effort had more subtle impacts also. The British royal family had long been known as the House of Hanover, named for the part of Germany from where King George the First had come in 1714. However, because of the wartime alignments the British royal family took the British name of the House of Windsor, which it still uses today. Hamburgers brought to mind the German city of Hamburg, so the dish became known as Salisbury steak, again a much more British sounding name. And Frankfurters wouldn’t do, named for Frankfort in Germany, so they became universally known in English-speaking countries as hot dogs.

As American troops arrived in Europe in late 1917 and into 1918, their numbers and fighting skills began to turn the tide in the Allies’ favor. These troops included an artillery officer named Harry Truman, whose unit helped win a decisive victory.

At this point I’d like to tell the story of someone my wife Charlene and I knew personally, Charlene’s great uncle, Theodore Boyd. Theo was a 24-year-old teacher in Tennessee when the war began. He enlisted and was sent to France, where he was trained as a military observer. In this role he would fly in an airplane, identify enemy targets, and send the information using another new invention, the wireless. He also had training in using a machine gun.

On September 14, 1918 (less than two months before the fighting ceased), Lieutenant Boyd engaged in combat with five enemy planes. Explosive bullets wounded both legs, his left foot, and his right elbow. In spite of his wounds he succeeded, by a remarkable display of courage and tenacity in keeping up the fire of his guns until the attacking planes were put to flight. During the return to the Allied lines, Lieutenant Boyd, although faint with pain and loss of blood, assisted his pilot in landing their disabled plane safely.

For his actions, Boyd was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. During his service, he was also awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action. Boyd spent the rest of the war recovering in a military hospital, and wound up marrying one of the nurses who attended him. After the war, Boyd took advantage of an early GI Bill which gave educational assistance to wounded veterans. He went to medical school and taught physiology at Loyola University in Chicago for 24 years. In 1947 he joined the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (or polio). He was assistant director of the research department for 20 years and then became director. When Jonas Salk applied for a grant to do research for a polio vaccine, “Uncle Doc,” as Charlene’s family knew him, was involved in the approval of the application. Uncle Doc attended our wedding in 1974. He died in 1986 at the age of 92.

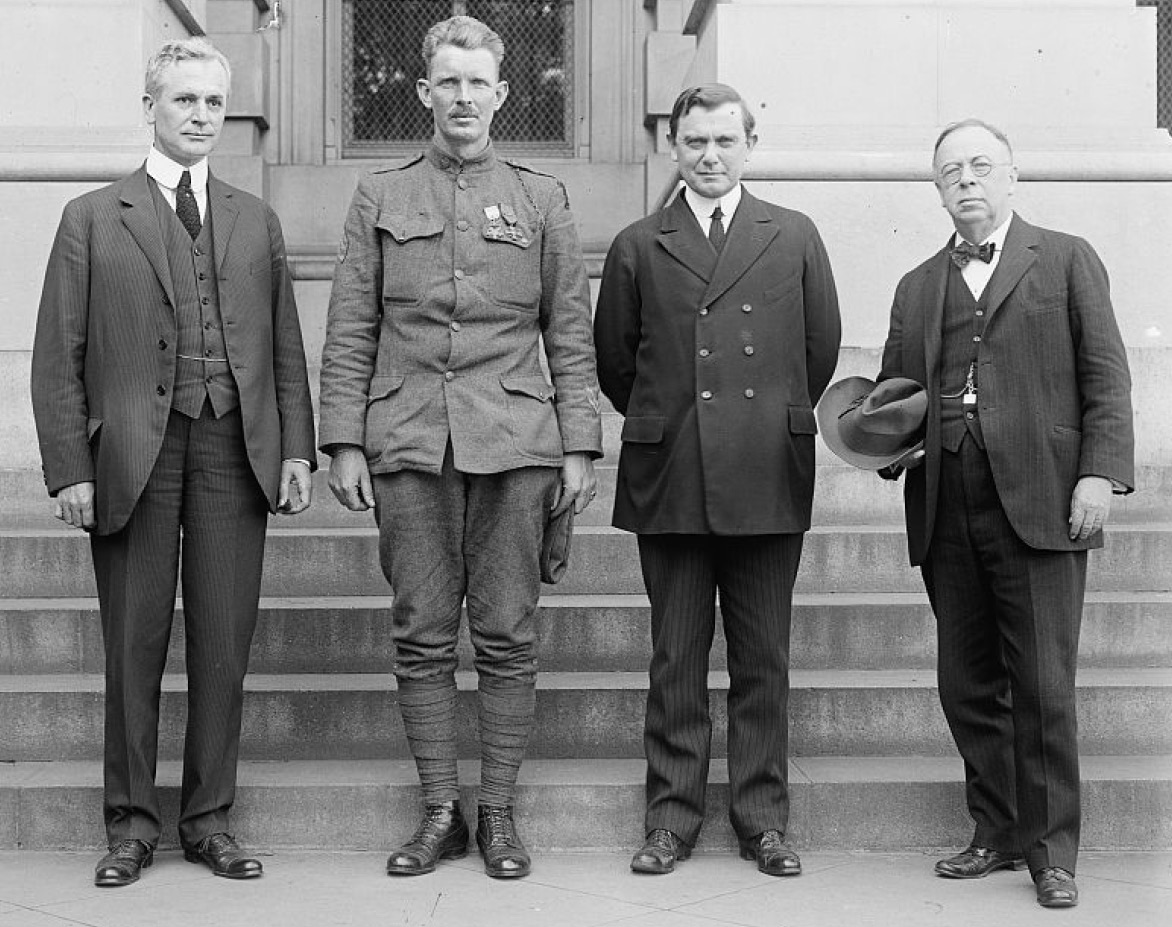

The greatest American hero of World War I was a quiet, thirty-one-year-old man from rural Tennessee, Alvin Cullom York. York had led a wild life before his conversion at a revival in 1914. When he was drafted for military service, York asked not to serve because he objected to war; but his request was denied. He eventually agreed to go into battle because it was a way to help stop others from killing.

In October of 1918, about a month before the end of the war, Corporal York’s unit of eighteen men was ordered to take a railroad line in the Argonne Forest. They misread their map and wound up behind enemy lines. A German officer surrendered to them even though he had the Americans outnumbered. German machine guns opened fire on their own men who had surrendered. In the process, they killed nine Americans. York, an expert marksman, was ordered to take out the machine guns, which he did. Eventually York and the other eight Americans who remained captured 132 Germans. York never claimed to have acted alone, but only two other soldiers were ever decorated for their part in the encounter.

News of York’s heroism made its way to the American military command. York received the Congressional Medal of Honor, was promoted to sergeant, and was welcomed back to the U.S. as a national hero. Civic clubs in Tennessee raised money to buy York and his new wife a house, but they were only partly successful and so York had to take out a mortgage to pay the remaining cost of the house. York dedicated his life to helping educate the children of his area. He founded and raised money nationwide for the York Institute, which eventually became a high school and vocational school. York never tried to make money off of his heroism. He resisted Hollywood offers to make a movie based on his life. However, after World War II began, York agreed to a movie deal in order to encourage young Americans to support their country in the war. The movie Sergeant York, which came out in 1941 and starred Gary Cooper, is a good representation of York’s life through his return to Tennessee from the war.

During World War I, a Communist revolution took place in Russia. The new Communist government withdrew from World War I and made a separate peace with Germany.

Finally, the Allies wore down Germany and the other members of the Central Powers, and the two sides agreed to an armistice or ceasefire to go into effect at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month–11 a.m., November 11, 1918, one hundred and six years ago next month. The costly fighting in that terrible war was finally over.

But the conflicts were not over. The story of the Versailles Peace Treaty Conference is worthy of another podcast, but we’ll try to summarize. President Wilson decided to attend the conference to push for his goals that included the self-determination of nations, a peace without victory, and the establishment of a League of Nations. But America’s European Allies had suffered greatly from the war, and their goal was to “Make Germany Pay.” In the end, they won out. Germany was forced to pay huge reparations to the victorious nations. Americans were tired of involvement in foreign wars, and the U.S. Senate defeated the peace treaty. The U.S. had to conclude separate peace treaties with its World War I enemies, and the United States never joined the League of Nations. Germany was not able to pay the reparations and defaulted on their debt. This plus the severe restrictions imposed on Germany’s military strength led to resentment on the part of many Germans. In the years after the war, Adolf Hitler manipulated the resentment in order to gain power. The renewed conflict eventually led to the Second World War starting in 1939.

Loss and devastation in World War I was unprecedented. The world had never seen anything on this scale before. Around the world, 65 million persons served in the military, 8 ½ million persons died in the war, and 21 million were injured. 116,000 Americans gave their lives. The war put the United States on the world stage as never before.

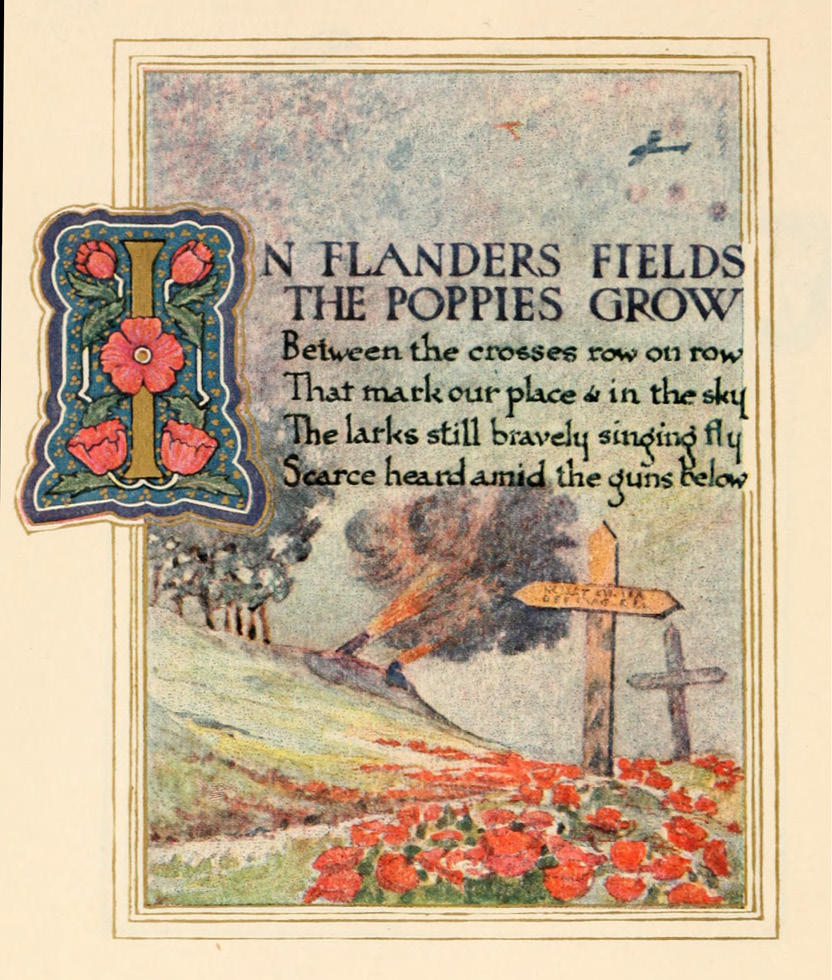

John McCrae was a Canadian physician who was involved in the war. He wrote a poem in honor of a friend who died in battle in 1915. McCrae died of pneumonia in January of 1918. Flanders is a region of Belgium, and the crosses referred to in this poem mark the graves of soldiers.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Silent days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

It is because of this poem that poppies became a symbol for remembering those who gave their lives in battle.

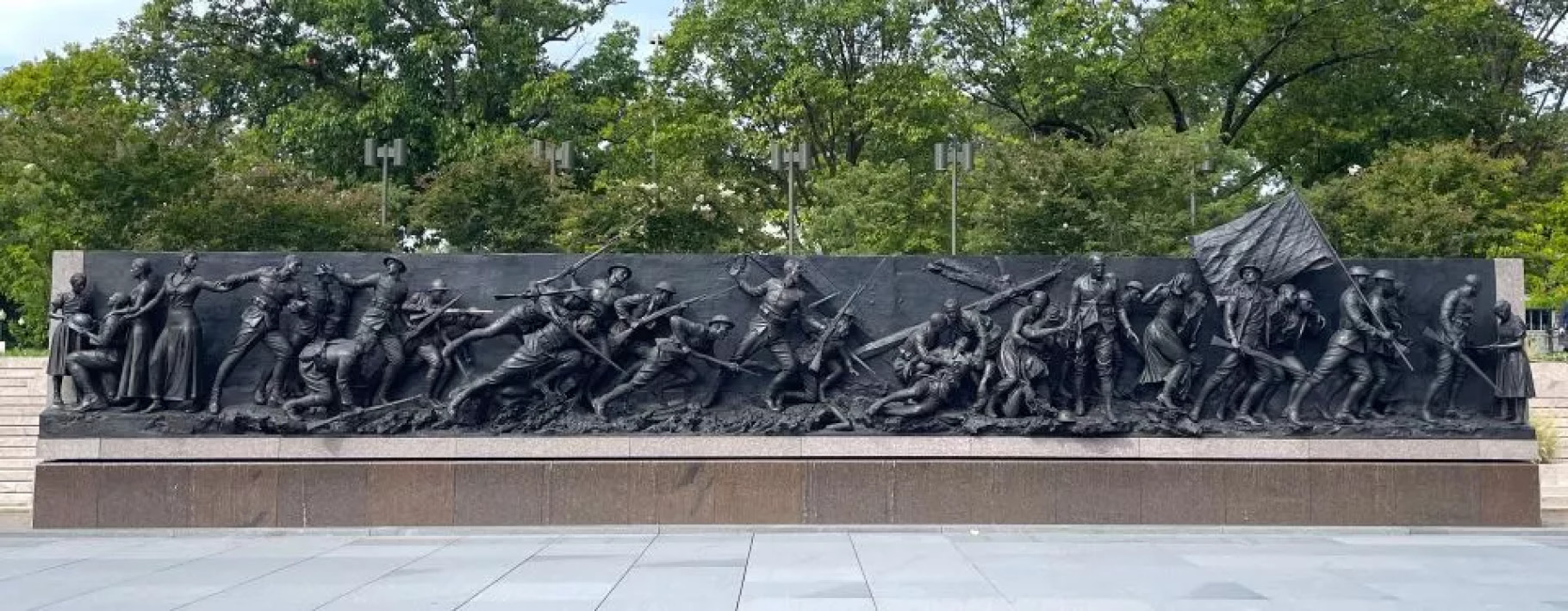

World War I is still making headlines. Just last month the World War I Memorial was unveiled in Washington, DC. This 58-foot-long relief sculpture portrays the successive phases of the war experience for a typical American soldier from joining the Army to coming home after the war.

Isaiah 2:4 says:

And they will hammer their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not lift up sword against nation, and never again will they learn war.

We haven’t yet learned how not to go to war. We still have to deal with alliances and brutal and costly war, and desire for revenge, and an imperfect peace. One war leads to another, and we still grieve for the dead who lie in fields marked by crosses. One day, we trust, as Isaiah 2 predicts, the mountain of the house of the Lord will be established as the chief of the mountains, that He may teach us concerning His ways. Let us pray that the hearts of mankind will be open to the Prince of Peace one day soon.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this episode.