Resources

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this podcast.

Transcript

Ray Notgrass: On today’s Exploring History podcast, I’ll look at a secret project of the former Soviet Union that had an ambitious goal: to map the world.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

As the Soviet Union was unraveling in 1989, its military men were selling off what they had control over for what they could get. American map dealer Russell Guy flew to Estonia with a quarter million dollars in cash. He bought thousands of Soviet-made maps, each one marked “SECRET.” Over the succeeding years Mr. Guy, as well as retired British software developer John Davies, and a handful of other people uncovered an amazing fact. During the Cold War, which lasted from 1945 to 1989, the Soviet military undertook one of the biggest mapmaking projects in history. Ordered by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, the goal of the tens of thousands of cartographers and surveyors who were involved in the project was to map the entire world, and many of these maps had amazing detail.

The Soviet authorities wanted detailed, accurate information about the huge country they ruled. The Communist leaders wanted to know the placement and condition of roads, the sizes of lakes and rivers, and the layout of cities. They wanted to determine the location of their natural resources and how they could develop them. Some of these maps not only included the location of forests, but also the size of the trees and the distances between the trees. They wanted to know how they could best move people and material where they might be needed.

Not all of the surveyors and cartographers survived their work on the project. One Russian surveyor reported finding a note left by a fellow surveyor on a tree trunk in Siberia in 1948 that indicated the man and his co-worker were near death. They likely did not make it home.

Moreover, during the Cold War the Soviets believed that their main enemy was the United States. As important as information about the Soviet Union was, they believed that information about the country they saw as their primary threat was even more vital. The Russians created detailed maps of the United States, including street maps of the major cities. The maps identified buildings along the streets and located bridges, as well as the construction materials and load limits of those bridges. The Soviets considered the maps so valuable that a Russian military officer could face prison or worse if he misplaced or lost one.

Where did the Soviets get such detailed information about the United States? Some of the information came from what our own government published through agencies such as the United States Geological Survey. Other information no doubt came from spies in our country. The Russians probably also utilized high-flying reconnaissance planes and spy satellites. The United States had U-2 spy planes flying over the Soviet Union. No doubt the Soviets had spy planes flying over the U.S.

But Soviet interest in maps didn’t end with the USSR and the United States. The Russians dreamed of dominating the world, so they wanted accurate maps of the entire world: cities, military installations, factories, roads, ports and airports—any information that could help if the opportunity came for them to move their tanks and troops into other countries. Again, some information was freely available, while they obtained other information by espionage.

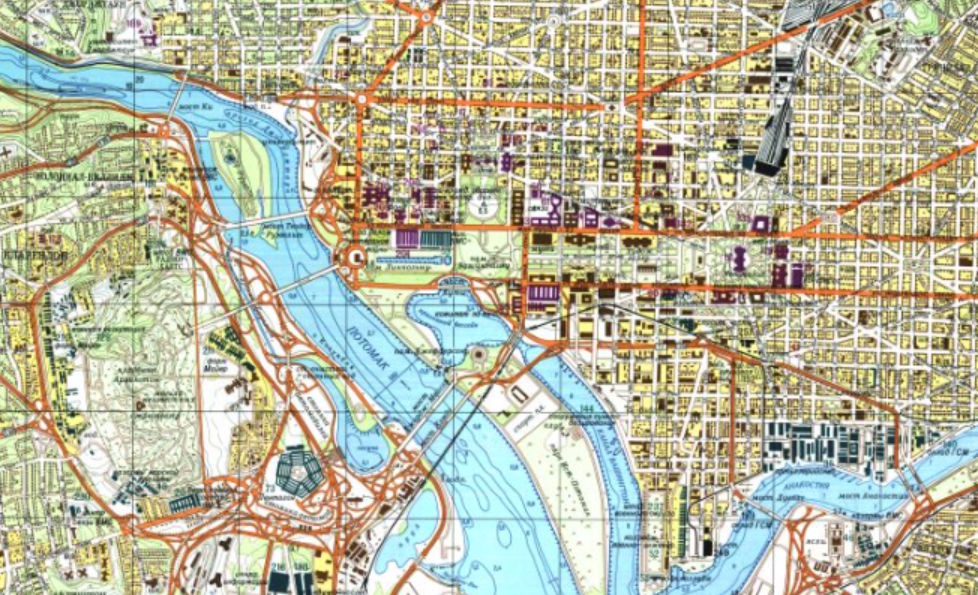

One expert on the subject of Soviet maps estimated that the Soviet military produced over one million maps. This is not one million copies of maps, but one million distinct, different maps, of which they made untold copies. Many of the maps show astounding details, such as the width of roads and the depth of lakes. I have seen images of some of these maps. It’s a little unnerving to see a detailed Soviet-era map of the Pentagon, for instance, with the roads around it and the Potomac River lettered in Russian with the Cyrillian alphabet. Or maps of New York; Chicago; San Francisco; San Diego; Raleigh, North Carolina; Beijing, China; Berlin, Germany; Paris, France; Halifax, Nova Scotia; and so forth, that identify specific buildings and military installations—all in Russian. In other words, they knew.

Sometimes the differences between Soviet military maps and maps from other sources are intriguing. For instance, a 1984 Soviet map of Chatham, England, shows a dockyard where the British Royal Navy built submarines. A British map from the same period shows a blank space there because the British did not want information about that location to become known—but the Soviets knew it anyway.

On the other hand, maps that were published in the Soviet Union and were available to the general Russian public were deliberately inaccurate in terms of distances, directions, and other details. The Communist government did not want such information available even to its own people but especially to others who might be able to obtain those maps.

Today there exists an international network of map dealers and collectors. A few map dealers around the world offer the Soviet maps for sale. Customers include governments, university libraries, and telecommunication companies that need to know the topography of an area where they plan to set up cell phone towers, for instance. The United States intelligence community used some of these Soviet-made maps to help our operations in Afghanistan in the early 2000s.

Of course, the United States had maps of the Soviet Union as well. We gathered information with reconnaissance planes and spy satellites, and we had our share of spies on the ground in Russia, too. But the information our government sought was more difficult to gather because the Soviet Union was such a closed society.

What do we know? What do our enemies know?

This is why maps are still important to us. And to them.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History to explore resources related to this episode.