[Crowd noise. Horn. Patriotic music in background.]

Ray Notgrass: It’s time for that quadrennial exercise in American democracy, when thousands of people spend millions of dollars and take several days to make a decision that’s already been made. Of course I’m talking about our national political party presidential nominating conventions. On today’s Exploring History podcast, we’ll talk about the history of conventions and how they work today. YAAAAY!

Voice: It's the most important election of all our lifetimes!

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening. In just a short time the two major political parties will hold their national conventions. As things now stand, the Republicans will meet in Milwaukee July 15th through the 18th, and the Democrats will meet in Chicago August 19th through the 22nd. At each convention, party delegates from the states will hear countless speeches, watch slickly produced videos, nominate presidential and vice-presidential candidates, and decide on a platform of positions on which party candidates will be expected to run in this fall’s election. State delegations and other groups will hold meetings, and party leaders will plan strategy. It’s all part of how we Americans choose our leaders, bash the other guys, and encourage voters to make the right choice in November. But the way conventions go today is not the way conventions have always gone. Conventions have seen times of drama and times of boredom. This is why we’ll try to give some historical perspective today.

Of course, the Constitution makes no reference to political parties or nominating conventions, even though they are vital to our election process. These institutions developed in the early years of our nation. George Washington was a unanimous choice to be the first president, but factions developed around John Adams and Thomas Jefferson even as Washington completed his presidency. Within a few years, lacking any other procedure, state legislatures nominated presidential candidates as did caucuses or meetings of party members who served in Congress. Voters didn’t have a chance to indicate their preferences until they voted in the fall. Some objected to this practice and complained that the political system was run by “King Caucus” as it was called. What some people wanted was a way to have a voice in the selection process which could also create the impression of a bandwagon carrying a candidate to the election.

Conventions of state political conventions came to be held in several places, but It was not until September of 1831 in Baltimore that a minor party, the Anti Masons, held a national convention (even though it was a relatively small meeting) to nominate a candidate for president. The main platform of the Anti Masons was to oppose the supposed nefarious influence of the Masons in American life and politics. For the 1832 presidential election, the convention nominated William Wirt, who it turned out, was a Mason, although he had been inactive for many years! Then in December of 1831, the National Republicans (who eventually disappeared into the Whig Party) met in Baltimore and nominated Henry Clay as their candidate for president. The sitting president, Andrew Jackson, and his Democratic supporters, decided to get into the act and create their own bandwagon, so in May of 1832 the Democratic convention met, again in Baltimore, and nominated Jackson for a second term. Jackson swept to victory in the fall election. This established the practice of holding a convention to discern and publicize what party leaders called “the will of the people.”

National elections in the United States are actually a combination of state elections with national publicity campaigns. State political parties and their conventions choose delegates to the national conventions. State party primaries didn’t come along until the early 1900s, so throughout the 1800s political bosses had a huge influence in choosing who the party nominees would be. Many times the parties did not have clear choices for presidential nominees before the national convention met, so the conventions saw a great deal of wheeling and dealing among factions and supporters of various candidates to try to obtain a majority of delegate votes that would grant the nomination to the party’s standard bearer.

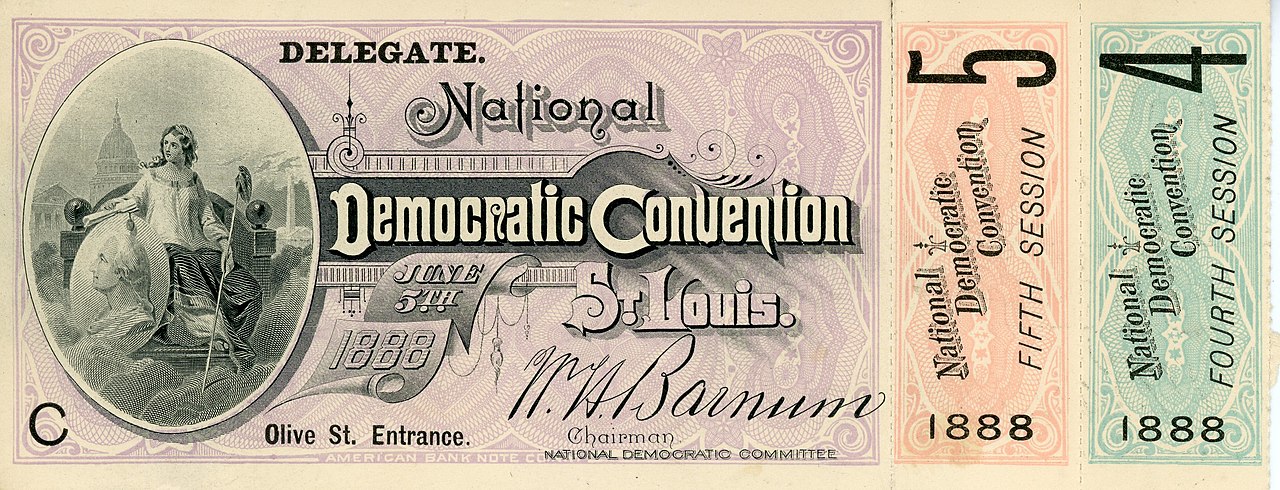

These 19th century national political conventions came to be quite a spectacle. The delegates, sometimes accompanied by their families, state and national politicians, reporters, and the general public would travel to the city that the party had chosen to host the convention, and fill up several downtown hotels. The convention site would be a large meeting hall, without air conditioning and without a public address system. The assembled thousands would try to hear what the convention chairman said and what those making speeches said above the crowd noise. The nominating process involved people making nominating and seconding speeches for several candidates, then having a roll call of the states. State delegations would cast their votes for one or more nominees, certain candidates would gain traction while others would fade, and the convention would eventually choose a nominee, usually after conducting several ballots or rounds of voting. Early on, the Democrats established a rule that required their nominee not just to have a majority of delegate votes but a two-thirds majority. This made for longer, more tedious conventions for the Democrats since it often took several ballots for one candidate to achieve a two-thirds majority. The Democrats changed that rule to requiring a simple majority in 1936.

For the roll call, the convention secretary would call on state delegation chairmen alphabetically by state to receive their vote totals. Each state chairman would often make a little speech about his state (such as “Illinois, the home of our greatest president, Abraham Lincoln, casts its votes for…” or “Montana, the home of majestic mountains and free flowing rivers, casts its votes for…”). If one roll call of the states didn’t produce the required majority, the convention would recess and party leaders would meet and try to make deals, such as offering support for one candidate in exchange for receiving a promise of a new law during the next session of Congress or having a state’s favorite son appointed to the next president’s cabinet. Then the convention went through the same state by state balloting process again, sometimes again and again. When one candidate received the required majority of delegate votes, the convention went wild. Those seeking the nomination would not attend the convention because that seemed too blatantly ambitious. Instead, a delegation of party leaders would go to the nominee’s home a few weeks later and make the official announcement that everyone already knew.

Modern conventions are the productions of the national party committees, the Democratic National Committee and the Republican National Committee, so you might hear references to the DNC and RNC during the convention season. The national committees award a certain number of delegates to each state, based on the population of the state and on the strength of the party in recent elections in that state. The Republicans have about 2,400 delegates and the Democrats have almost 5,000. Of course, smaller political parties, often called third parties, have conventions also, but their productions are much smaller and less grand.

The thing is, these days, we all know who the party nominees are going to be because the delegates chosen through state primary elections usually provide the majority of delegates needed for a candidate to receive the nomination. So the convention does not so much select a nominee as crown the nominee that has already been chosen. It has been years since a convention produced any real surprise regarding the nomination. But let’s look back at some specific conventions that did provide some drama and surprises.

In 1844 former president Martin Van Buren was the leading candidate for the Democratic Party nomination going into the convention. But Van Buren announced that he was opposed to the annexation of Texas, a position that hurt him among southern Democrats. As the convention went through ballot after ballot trying to reach a consensus, one name began to emerge as a possible consensus candidate: James K. Polk of Tennessee. Polk was a close friend of former president Andrew Jackson, a former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, and a former governor of Tennessee. He had sent personal representatives to the convention hoping that their influence would help him secure the vice-presidential nomination. Polk’s support grew during the continued balloting. On the 9th ballot, Polk received the nomination, and he went on to win the presidency that fall. Polk was the first of what was called a dark horse candidate, meaning a horse that came out of the dark–out of nowhere–to win the race.

1844 also saw a significant advance in technology highlighted at the major party conventions that year, both of which were held in Baltimore. That technology was Samuel Morse’s improved telegraph, which signaled the convention results instantaneously to Washington. People were amazed that news could travel faster than a horse could carry it, and communication hasn’t slowed down since.

The 1860 conventions reflected the divided state of the country at the time. Abraham Lincoln received the Republican nomination at the convention in Chicago on the third ballot. That one was straightforward enough. But the Democrats were divided over the question of slavery. The Democrats met in Charleston, South Carolina, in late April into early May and were deadlocked. The leading candidate, Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, received a majority of delegate votes but not the required ⅔ majority, so the convention adjourned. They reconvened in Baltimore later in May, but many Southern delegates either boycotted or walked out. Douglas was too moderate on slavery for them. The party had a mathematical problem, though. They had less than ⅔ of the delegates who hd been at the original convention, so technically they couldn't select a nominee. The convention agreed to drop the rule for that convention, and Douglas was nominated. Then a few weeks later, the Southern delegates who had boycotted or left the earlier convention met and nominated John C. Breckenridge, the sitting vice president from Kentucky, on a pro-slavery, states rights platform.

Finally, a group that called itself the Constitutional Union Party held a convention. This group of former Whigs and others did not address slavery directly and tried to appeal to moderates. The party nominated John Bell of Tennessee, who received 39 electoral votes in the election. In this divided field of candidates, Lincoln received just shy of 40% of the popular vote and a clear majority of electoral votes and won the election.

Another dramatic Democratic convention took place in 1896 in Chicago. The key issue that year was whether the federal government should coin silver to increase the money supply that had previously been based strictly on gold. Farmers and debtors wanted the silver coinage to help them pay off their debts with more available money. Financial interests wanted to maintain the gold standard to avoid inflation. Both parties were divided over the issue. At the Democratic Party’s convention that year, William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska gave the keynote address. Bryan was an attorney, a former congressman, and the editor of an Omaha newspaper. His speech was a ringing endorsement of the coinage of silver and a stinging denunciation of financial interests. His closing statements were: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns. You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” At this the crowd went wild. Bryan had not been a declared candidate for the nomination, but he had been working behind the scenes to build support for the nomination. At 36 years of age, Bryan became the youngest person ever to receive a major party’s nomination, only a year older than the Constitutional minimum. He received the nomination but lost to Republican William McKinley in the general election.

Let’s move on to 1924. The Republicans were riding high with Calvin Coolodge in the White House and a majority in both houses of Congress. The bitter taste of Democrat Woodrow Wilson’s failed attempt to get the United States to join the League of Nations after the Great War (what we now call World War I) was still in many mouths. The Democrats had no leading contender for the nomination when they met in Madison Square Garden in New York City. The delegates voted–and they voted, and they voted. Finally, after 16 days and 103 ballots, the convention selected John W. Davis. Davis was an attorney, a former congressman, and a former solicitor general under Wilson. 103 times the convention went through the roll call, 103 times the convention secretary tallied the votes, until Davis received the required ⅔ majority. In the fall election, Coolidge trounced Davis, who received only 25.6% of the popular vote compared to Coolidge’s 71.9%.

But the 1924 Democratic convention did witness a significant emotional event, the political return of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Roosevelt had been the party’s 1920 vice-presidential candidate. Then in 1921 he was stricken with polio and became unable to walk without assistance. Most people believed that Roosevelt’s political career was over. One man who didn’t believe that was Franklin Roosevelt. Through hard work and rehabilitation, Roosevelt did regain his ability to walk using heavy leg braces and sheer willpower. He made his way to the convention podium and gave a nominating speech for Al Smith of New York. Partly as a result of that stirring performance, Roosevelt was elected governor of New York in 1928, reelected in 1930, and then won the presidency in 1932.

Another technological advance that came to the front during the 1920s was the advent of radio. In the early years of the decade, only a few thousand people had radios; but by the end of the decade, millions of Americans could listen to the speeches and other events of the conventions. The Republican convention in Philadelphia in 1940 was the first to provide television coverage, again to only a few thousand sets, but the door was opened.

1948 provides an example of how just about everything could go wrong for a nominee yet he could still win the election. That year Harry Truman was completing the term that he had begun when he became president after the death of Franklin Roosevelt. He was hoping to be elected to a full term in his own right. But Truman had been president long enough to displease a lot of his fellow Democrats by his performance in office. His big failing was that he wasn’t Franklin Roosevelt, who was every Democrat’s ideal. Truman had enough clout in the party to obtain the nomination, but it appeared his clout ended there. On the evening he was to give his acceptance speech, the convention had so much turmoil that his speech was delayed until 1:54 a.m., hardly prime time for the radio and small television audience. But beyond that, the party split three ways. Conservative southern Democrats thought that Truman was too liberal, so they formed the Dixiecrat Party and nominated Strom Thurmond of South Carolina. Liberal Democrats thought Truman was too conservative, so they nominated former vice president Henry Wallace on the Progressive Party ticket.

All that didn’t stop Truman from mounting one of the great campaigns in American history. In his acceptance speech, Truman said that he would call the Republican- majority Congress into special session and dare them to take action on matters they had been complaining about. Of course, they didn’t take action, and then Truman embarked on a long whistle stop campaign by train in which he blasted the “Do-Nothing” Congress. Still, just about every pollster and expert expected Truman to lose the election to Republican Thomas Dewey. One person who didn’t believe that was Harry Truman. The morning after the election, sure enough Truman had won.

Now the events at the national conventions are carefully scripted to take place during evening prime time television hours for the parties to be able to put their best foot forward for the viewing audience.

I could tell many stories about conventions past. In 1964, less than a year after President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, the Democratic convention planned to present a tribute film to the late president. Scheduled to make a speech to introduce the film was the late president’s brother, Robert Kennedy. When Robert Kennedy mounted the podium, the convention burst into applause that lasted 22 minutes. Imagine standing and applauding for 22 minutes. It was an emotional moment for everyone involved.

I must tell about the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. On March 31 of that year, President Lyndon Johnson announced that he would not seek re-election. His policies in the Vietnam War had created strong opposition even within his own party. First Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota and then Senator Robert Kennedy had announced their candidacy for the nomination. But then Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated on April 4, and then on June 5 Robert Kennedy was assassinated and died the next day. It felt as though the party and the country were bordering on chaos. Antiwar protesters promised to march in the streets of Chicago hoping to disrupt the convention. As the convention met, thousands of protesters and thousands of police officers clashed in physical conflict. The protesters chanted, “The whole world’s watching,” as television commentators criticized the harsh response of the police. It was a scene never before or since played out on the nation’s televisions. Vice President Hubert Humphrey received the nomination, but he lost a close election to Richard Nixon that fall.

Then there is the matter of the vice presidential nominees. For many years, the pattern was that after the presidential nominee was chosen, he would meet with his advisers and perhaps a few possible choices, and the next day would announce his selection for the second spot on the ticket. The goal was usually to provide philosophical and geographical balance to the party’s ticket. If the presidential nominee was from the Northeast, the vice presidential nominee would be from the Midwest. The vice presidential nominee might be a little more conservative or a little more liberal than the presidential nominee to try to attract more voters to the ticket. The convention would endorse the choice that evening, then the vice-presidential and presidential nominees would give their acceptance speeches. A common criticism of this process was that very little time and consideration was given to choosing the person who would be one heartbeat away from the presidency.

In 1976, Ronald Reagan was battling incumbent president Gerald Ford for the Republican presidential nomination. A few weeks before the convention, the conservative Reagan announced that if he won the nomination he would select moderately liberal senator Richard Schweiker of Pennsylvania as his running mate. This was an obvious attempt by Reagan to broaden his appeal among voters in the hopes that he might swing enough delegates to him at the convention. The move didn’t work, and Ford got the nomination. That 1976 Republican convention was the last time there was any serious contest for the nomination as the convention began.

Then in 1984, former vice president Walter Mondale was behind in the polls as the conventions neared. In a bold move, Mondale announced that his vice presidential choice was Congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro of New York. Mondale made the selection not so much to balance the ticket–Mondale and Ferraro were both liberal–but to open a political door, since Ferraro would be the first woman to be placed on a major party’s national ticket. The move didn’t work, however, and Reagan trounced Mondale in the November election.

Since that time it has generally been the case that party nominees announce their vice presidential selections at least a few days before the conventions begin.

It might seem that the conventions have simply come to fit a routine mold, but once in a while a dramatic scene will emerge. The 2020 conventions broke out of the norms because of the COVID pandemic. The conventions became virtual events that year

This year the conventions just might not fit the long-standing pattern either. We might be in for some surprises as the delegates assemble.

We could probably all think of ways that the American nominating and election process could improve, but change does not come easily. It’s hard to imagine the literally billions of dollars that are now spent on election year campaigns and the hundreds of hours of television and Internet coverage that will be presented to us from now until election day. But it’s still a great country we live in, and the basic greatness of our country enables us to make it through intact. God bless us as we do it again this year.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History for more information about political parties and conventions.