Ray Notgrass: On today’s Exploring History podcast, we’ll look at America’s newest national holiday, what has been called America’s second Independence Day. I’m referring to the day known as Juneteenth.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening, and Happy Father’s Day coming up on the 16th. God bless you in your vital role as father in your family.

The date was June 19, 1865. The place was Galveston, Texas. At the time, Galveston was the largest city in Texas. It was a busy port city, the place where the valuable harvested crop of cotton was shipped out from the state to textile factories elsewhere. Texas was the westernmost state in the Confederacy and had seen little fighting in the Civil War.

African American dockworkers in Galveston had heard some news from incoming ships, and they had begun to celebrate. Their white overseers strongly reprimanded them and ordered them to concentrate on the jobs they were supposed to do. But the rumor they had heard was true, and it gave them good reason to celebrate.

On that day, Union army general Gordon Granger arrived in the city along with 2,000 troops. Granger had come to assume command of all Union forces in Texas. Union troops were still needed in Texas to maintain order. Even though Confederate general Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Union commander Ulysses S. Grant almost two months earlier, some Confederate soldiers had until a few days before still been active in Texas. In fact, a skirmish between Union and Confederate troops had taken place about a month earlier, on May 13, 1865, at Palmito Ranch, Texas. The participants didn’t know it at the time, but this turned out to be the last battle of the Civil War. The remaining Confederate troops in Texas surrendered at Galveston on June 2, 1865, just over two weeks before General Granger’s arrival.

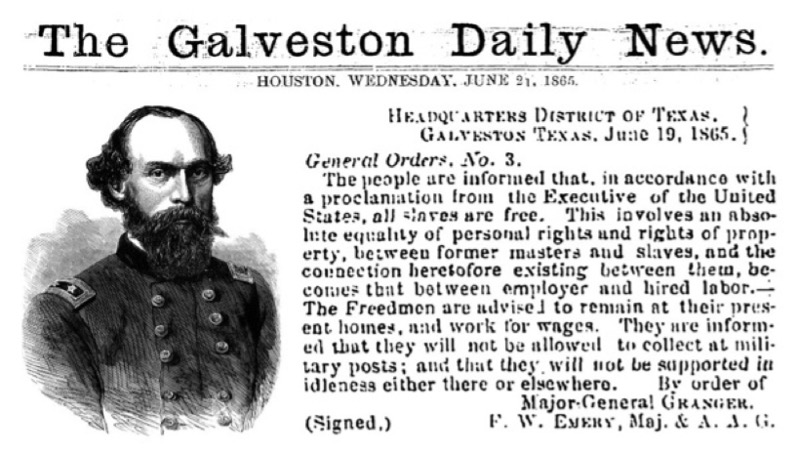

But Granger had bigger news than the arrival of a new force of Union soldiers. Granger had a proclamation to announce, General Order Number 3, and this is what it said:

The people [of Texas] are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Just about everyone who heard or read the proclamation was stunned. Slavery was abolished. All enslaved persons were free. The peculiar institution, as Southerners often called it, that had kept 250,000 persons in bondage in Texas was ended. The practice that had sustained much of the state’s economy and that had helped to define how society operated in Texas was no more. A major motivation for white Americans moving to Texas earlier in the 1800s had been to own sizable tracts of land on which they could practice slavery. The constitution of the short-lived Republic of Texas and later that of the newly admitted state of Texas protected slavery and placed severe restrictions on free black persons in the state.

Many white persons in Texas at the time believed that black persons were inferior and that slavery was right and proper. So the general order that Granger announced on that June 19th was a shock, and the statement of equality of rights was an even greater shock. Both black persons and white persons were going to have to learn how to live their lives in a different way, on the basis of true freedom and true equality for all people. That new basis of freedom and equality would be a century in coming fully, but the foundation was laid that day in Galveston.

The practice of slavery has marred human civilization from its earliest days. Nations around the world practiced slavery. It was a common aspect of life. Usually, enslaved persons were prisoners of war that victorious armies took from defeated nations. Victorious African tribal leaders, for example, enslaved members of defeated African nations. Race was not an issue in those situations. The issue was power and domination. Because enslaved persons came from all walks of life, some were highly skilled, and their masters entrusted them with important responsibilities. Enslaved persons came from many nations and ethnic groups. But the thing to remember about anyone who was enslaved was that they were not free. They were held in bondage and were considered property. Enslaved persons could sometimes gain their freedom, by grant of their master or by buying their freedom; but until and unless this happened, they were in bondage.

Slavery became less common in Europe during the Middle Ages. The practice of serfdom largely replaced slavery, although the conditions for serfs were mostly the same. The practice of slavery reemerged when Europeans began exploring Africa in the late Middle Ages. European explorers to Africa captured people and brought them back to Europe, where they were sold into bondage. Sometimes tribal leaders in Africa cooperated with Europeans by selling captives to them.

The practice of slavery expanded when Europeans began to explore the New World. Traders brought enslaved persons to the English colonies in America in the early 1600s. Europeans began sugar plantations in the Caribbean region and shamefully used slavery to provide their workforce.

Only a relatively few people opposed the practice of slavery during the American colonial period, and these few were considered extremists. In the new United States, states in the North gradually ended the practice, but it continued in the South, especially on the large plantations.

The views that people held on the practice of slavery covered a wide spectrum, from those who flatly opposed it to those who defended it as a positive practice that made economic sense and that lifted captives from Africa out of pagan ignorance and poverty. Southern leaders believed that their region was economically dependent on slavery despite its detrimental effects. Slavery provided relatively cheap labor, but the practice of slavery devalued human life. An economy based on the labor of enslaved persons was never as productive as one based on the labor of free people who could innovate and work hard to improve their lives and the lives of their families. The practice enabled and justified indolence on the part of white people, and it allowed and encouraged white people to treat black people harshly. Many white persons held the erroneous belief that black persons were intellectually inferior and that the two groups could never coexist as social equals.

Some Americans were troubled in their consciences about slavery but continued to accept it. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, wrote in the Declaration of Independence “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” But Jefferson held people in slavery, as did many of the founding fathers and many of our first presidents. Many American leaders struggled in their hearts over what to do about slavery, but they continued to accept the practice. Gradually, in the first half of the 1800s, the once extreme, unthinkable position of advocating the abolition of slavery became more mainstream. The 1860 Republican candidate for president, Abraham Lincoln, declared, “If slavery is not wrong then nothing is wrong.” Still, he did not at that point advocate ending slavery where it existed. Lincoln did not believe that the president had the authority to do so. He only opposed extending slavery into the territories where it could eventually become the practice in newly formed states. By contrast, most Southern defenders of slavery were fierce in their defense of the practice and in the right of Americans to take their–quote–”property”--unquote, as they called enslaved persons, into the territories. According to the 1860 federal census, almost four million persons were held in slavery in the United States.

But the tide of human opinion on the practice of slavery had begun to shift. Haiti abolished slavery in 1804. Britain outlawed slavery throughout its empire in 1833.

When the Civil War began, Lincoln said that his purpose was not to end slavery but to preserve the Union. As the war progressed and the Union found only intermittent success and frequent defeat on the battlefield, Lincoln came to believe that he had to do something to give the Union a moral cause to pursue victory and to disrupt life in the Confederacy. That cause became the abolition of slavery. Even then, though, abolition was limited and gradual. It was a multistep process.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation. He declared that enslaved persons in the still rebellious areas of the Confederacy were “thenceforth and forever free.” He promised that the executive department of the federal government would defend their freedom. But the order did not apply to states still in the Union that practiced slavery or to areas of the Confederacy that Union forces had taken, such as Tennessee. Enforcement of the proclamation would be difficult, since the areas affected did not recognize Lincoln’s authority. Life and government in the chaotic South became even more chaotic. But many enslaved persons did walk to freedom by making their way to Union army positions, and some formerly enslaved persons joined the Union army.

As the war progressed, Union forces won more victories. The Confederacy’s military abilities and resources declined. The eventual outcome of the war became more obvious. Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment that outlawed slavery on January 31, 1865. President Lincoln submitted it to the states for ratification the next day. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered the Confederate forces under his command. Scattered Confederate units still remained in the field, but for all intents and purposes the Southern rebellion was over. So also was the practice of slavery in theory, but it continued in Texas.

Texans who kept people in bondage did not tell the enslaved persons they held about the Emancipation Proclamation, and they continued to hold them to forced labor. This is why General Granger made the proclamation he did in Galveston on June 19, 1865, two and a half years after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Even so, some Texans still did not free the people they kept in bondage until representatives of the federal government forced them to. Some cynically kept people in bondage long enough to bring in the harvest that year before releasing them. Enough states ratified the Thirteenth Amendment for it to become part of the Constitution on December 6, 1865. Slavery in the United States was now finally, officially over in the whole country.

Enslaved persons who were in Galveston on June 19, 1865, and over succeeding weeks those who were enslaved throughout Texas, understood the meaning of Granger’s announcement. They were now free. The formerly enslaved persons did not turn on their white neighbors or even their former masters but got about the business of reuniting families, solemnizing marriages, finding work, and seeking out opportunities for education, which had been denied them as enslaved persons. On March 3, 1865, Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau to assist those who had been held in bondage in the transition out of slavery. An office of the bureau opened in Galveston two months after the June 19 declaration, but the office was underfunded and understaffed, and white Texans provided little support for its efforts.

In 1866 people who had once been in bondage gathered in Galveston to celebrate what they called Juneteenth, a combination of June and nineteenth. The practice of observing the day spread from there to other cities and towns in Texas and then to other states. Celebrations included worship services and sermons, parades, picnics, and speeches. Many enslaved persons had clung to their faith in Jesus as the One who gave them real freedom. They compared their situation to that of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. Thus the newly freed formerly enslaved persons saw their freedom not merely as a political or governmental decision but as a gift from God. The practice developed of buying or making new clothes for the Juneteenth celebrations to symbolize their new lives as free persons. These celebrations took place near rivers or wherever they could gather because black persons were not permitted to use public facilities that were available only to white persons.

This kind of discrimination characterized the late 19th century and early 20th century for black Americans. Those who had been enslaved were now free, but the attitude of many white people, who held political power, was: We can’t own you as slaves anymore, but we’re going to restrict your rights and your lives as much as we can. Immediately after the Civil War, black persons could vote and hold office, but even those rights were taken away in subsequent years. Black persons had to cope with what came to be called Jim Crow laws enforcing segregation. Here’s where that term came from.

Before the Civil War, one common form of entertainment was minstrel shows, in which white entertainers blackened their faces and pretended to be black. They performed as stereotyped black persons that white audiences wanted to see. One such performer was Thomas Rice. About 1830, Rice performed a show in blackface as the character Jim Crow, a clumsy black man who sang and danced. After the Civil War, the term came to be a label for the discriminatory, segregationist system of laws that made black Americans second-class citizens, a system that in effect treated all black persons as Jim Crows, people who didn’t deserve to be respected.

Black Americans wanted and deserved equal rights, but these were a long time in coming. The 1896 Supreme Court decision Plessy versus Ferguson was a step backwards in this struggle, as the Court upheld the practice of states maintaining separate but equal facilities for the races. Schools, railroad cars, and other public facilities were separate but in fact were hardly ever really equal. Organizations such as the NAACP–the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People–tried to use court cases to chip away at discrimination, but few government leaders supported their efforts.

During World War II, black Americans served with distinction, but almost exclusively in segregated units. On the domestic front during the war, many black Americans took part in what they called the Double V movement: one V for victory abroad, and one V for victory at home. It was ironic to them that they fought overseas for freedom from oppression but at home they still faced discrimination and oppression. In the years after the war, with the patient guidance of black leaders and the patient and often self-sacrificial efforts of many black Americans, the situation began to change. The 1954 Supreme Court decision Brown versus Board of Education outlawed segregation in public schools, although the actual implementation of this decision took many years. The 1964 Civil Rights Act was a major step in achieving equal treatment for all Americans.

In 1872 black Texans raised money to buy a location they called Emancipation Park in Houston. Ten acres in size, it is the oldest park in Texas. Originally it was only used for Juneteenth celebrations. At the time, it was the only park in Houston available to African Americans. The park had to close after a few years because of a lack of funds to maintain it. The owners of the park donated it to the city of Houston in 1916, and the city made it a municipal park in 1918. But again it fell into disuse. The efforts of many people revitalized the park in 2007, and it now has extensive and beautiful facilities. In 2017 the city renamed the street on which the park is located Emancipation Avenue. Other cities have also established parks to honor Juneteenth. In 1979 Texas was the first state to make Juneteenth a state holiday. It was first observed in 1980. In 2021 Congress established Juneteenth as the 12th national holiday.

In the curriculum that Notgrass History publishes, we tell the whole story of America, the pleasant and the difficult, our successes and our failures. We include literature that reflects the experience of black Americans. America has definitely changed for the better in the context of our topic today, but progress does come slowly and with difficulty.

To close this discussion of Juneteenth, our nation’s second Independence Day, I’d like to quote the closing passage of Martin Luther King Jr’s “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered at the great civil rights March on Washington in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963.

King spoke of the day when all Americans would enjoy the freedom we so often talk about. He said:

. . . This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning: "My country 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim's pride, From every mountainside, let freedom ring!" And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the peaks of California.

But not only that:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

When we let freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thank you for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History for videos and other resources related to Juneteenth.