Ray Notgrass: On today’s Exploring History podcast, I’ll talk about someone who went from jail to the Supreme Court, who accomplished something that few Americans have, who was probably one of the most influential people in American government during the 1930s and 1940s. His life and career teach us about becoming a citizen who makes a difference, and yet he is someone you’ve probably never heard of.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening. So who is this amazing person I’ve referred to? His name was Fred Vinson, a man who spent 30 years in public service during the twentieth century. Allow me to introduce him to you.

Frederick Moore Vinson was born in 1890 in Louisa, Kentucky, a small town in the Appalachian Mountains of Eastern Kentucky on the border with West Virginia. In his campaign speeches early in his career, Vinson jokingly said that he was born in a jail. That wasn’t exactly true but it was almost true. Vinson’s father was the county jailer, and his family lived in a house directly behind the jail. This house is where Fred was born.

Young Fred had a couple of influences that encouraged a career in the law. First was his father’s job as jailer. In addition the Vinson family was friends with the local judge, who often let Fred sit beside him on the bench while he was holding court. Fred was a good student in school and loved sports, especially baseball. He was also quarterback of his high school football team. A major influence in Fred’s early life was his mother, who always believed in him.

Fred went to Kentucky Normal School and then transferred to beautiful Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, where he went on to attend law school. He graduated from law school in 1911 with the highest grade point average any student had achieved to that time. He went back home and opened a law practice in Louisa, where he became known as the best checkers player in town. The town council named him city attorney in 1913.

When the Great War began–what today we call World War I– the Army rejected Vinson because he was underweight–he was tall but skinny. So instead he gave speeches on behalf of bond drives and Red Cross appeals. The Army finally deemed Vinson to be acceptable in 1918 and he enlisted, but then the war ended later that year, and he was discharged.

In 1921 Vinson was elected commonwealth attorney (the Kentucky title for district attorney) for a three-county district. Two years later he married Roberta Dixon, who was also from the town of Louisa.

Vinson was elected to Congress as a Democrat in a special election in January of 1924. He was 34 years old. He was elected to a full term as a congressman later in 1924 and reelected in 1926, despite the fact that the Republican Party was strong nationally that year.

As a congressman, Vinson did his homework on bills that came before Congress, and in the House of Representatives his fellow congressmen recognized Vinson as an expert on taxation and fiscal issues. Vinson was a conservative Democrat, but in 1927 he broke precedent and urged federal assistance for flood victims. His position was ahead of its time and Congress did not provide this relief.

Then Vinson was defeated in his 1928 reelection bid. Al Smith was the Democratic candidate for president that year. Smith was a Roman Catholic from New York who opposed Prohibition. He was not popular in rural Kentucky and he took Vinson down with him. It was the first and only time that Fred Vinson lost an election.

Vinson returned to his law practice in Louisa but always planned to run for Congress again.

Then in 1929 came the stock market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. Now it was the Republicans who were unpopular. Vinson won in 1930, defeating the Republican incumbent who had defeated him in 1928. Vinson won reelection in the Roosevelt landslide of 1932 and was elected again in 1934 and 1936. Vinson didn’t know it at the time, but 1936 marked his last political campaign.

Serving once again in the U.S. House of Representatives, Vinson was an advocate for the tobacco and coal industries, both of which were big businesses in Kentucky, and he also favored increased benefits for veterans. He advocated organizing all branches of the military under a single Cabinet-level Secretary of Defense. At the time, the Cabinet included a Secretary of the Navy, who also oversaw the Marine Corps, and a Secretary of the Army, who oversaw the new and growing Army Air Force. On this issue Vinson was again ahead of his time. The secretary of defense eventually became a cabinet level position, but only after World War II. Vinson became a big supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal. He helped shape the Social Security program that Congress created as part of the New Deal. Vinson even supported FDR’s court-packing plan for appointing additional justices to the Supreme Court. Roosevelt proposed this plan because the Supreme Court had struck down several New Deal programs as unconstitutional, and Roosevelet wanted to appoint additional justices so a majority on the Court would support the New Deal. But the plan was so obviously partisan that Congress never approved it.

In 1938 President Roosevelt nominated Vinson to serve as a judge on the Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. Roosevelt appointed Vinson for this judgeship to reward him for supporting the New Deal. However, after Roosevelt failed in his attempt to pack the Supreme Court with more judges who supported the New Deal, he decided to try to reshape the judiciary another way -- by appointing judges who would support his agenda. Before Vinson took his seat on the court, however, he had some more work to do in Congress. Vinson waited 5 months after his confirmation to take his seat as a judge. He wanted to steer a tax bill through the House of Representatives first. When Vinson became a federal judge, he was 48 years old and had been in Congress for 12 out of the previous 14 years. Vinson loved the world of politics. While he was a judge, administration and congressional officials still consulted him about legislation in Congress. Most people would frown on this practice today.

In his five years on the DC Circuit Court, Vinson participated in 439 cases. His philosophy in dealing with the issues he faced was what we would call judicial restraint, not judicial activism. He tended to accept the actions of Congress and stood by legislative intent. Among the cases he heard were those that involved laws he had helped pass while in the House of Representatives.

Building on the expertise Vinson had developed while in Congress, he then became involved in the Roosevelt administration’s economic policies during World War II. While he was on the DC Circuit Court, in March of 1942 Supreme Court Chief Justice Harlan Stone appointed Vinson to be Chief Judge of the Emergency Court of Appeals. The Emergency Court heard appeals of cases involving the Emergency Price Control Act. These were usually complaints involving price ceilings for commodities and rent ceilings that the Roosevelt administration had imposed under the authority of the act. Vinson served on the Emergency Court of Appeals for 14 months, and by far most of his decisions upheld administration decisions.

Then in May of 1943, Roosevelt took Vinson out of his judicial robes and into a direct role in his administration by naming him Director of the Office of Economic Stabilization. In his almost two years in this role, Vinson in practical terms oversaw the wartime American economy. Vinson’s primary responsibility in this office was to control inflation by regulating price, wage, and salary increases. Then Vinson left that job to become Federal Loan Administrator, where he served for about a month, then he took on the role of director of War Mobilization and Reconversion for a little over three months.

Fred Vinson was present when Harry Truman took the oath of office as president on April 12, 1945, after the death of Franklin Roosevelt. Vinson was a friend and adviser of Harry Truman, who had a great respect for Vinson. He often attended Truman’s poker games in the White House.

President Truman nominated Vinson to be Secretary of the Treasury, an office he held for just under a year. He succeeded Henry Morgenthau, who resigned after having served 12 years as Treasury Secretary. At the time Morganthau said, “If I had to pick among all the people for my successor, I would have picked Fred Vinson.” As I mentioned, Vinson liked being back in the rough and tumble of the political world. He was happy to serve and sacrifice as a federal judge for the war effort, but he found the judiciary too easy and tame for his taste.

Vinson headed the Treasury Department that had a workforce of 97,000 people. He proposed tax cuts to aid in the transition from a wartime economy to a peacetime economy. He oversaw the creation of the Council of Economic Advisors, a group that still advises the president on economic matters today.

Because of his rapid and frequent moves throughout the federal government, Vinson became known during this period as “Available Vinson.” He was willing to move to a new position wherever he was needed and appointed. For instance, in July of 1944 Vinson was the chairman of the American delegation to the Bretton Woods Conference, which involved representatives from 40 countries who attempted to shape the postwar economic world by establishing economic stability and cooperation. Out of the deliberations at the conference came the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

In this dizzying succession of positions in the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, Vinson was a key player in helping prevent runaway inflation, encouraging lower taxes, defining the role of government, and balancing all of the often competing factors in the American economy.

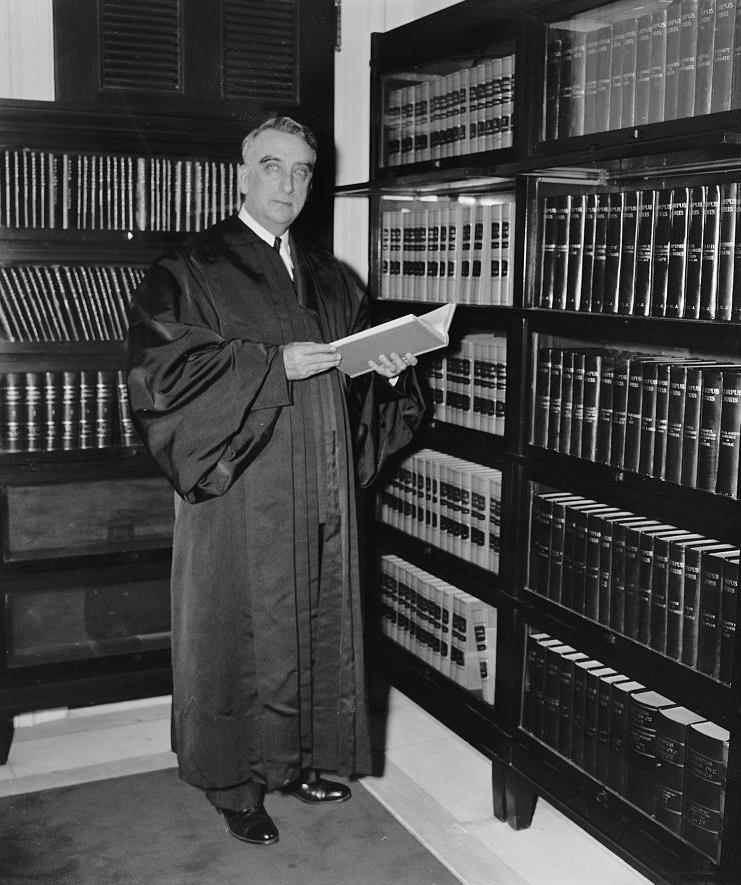

Then in June 1946 President Truman nominated Vinson to be chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, to succeed Harlan Stone. This was the last time that a president has nominated a current or former member of Congress to the Supreme Court. The Senate confirmed Vinson by a unanimous voice vote, and he took the oath of office that same month. A big reason why Truman wanted “Available Vinson” to be chief justice was that the Court was plagued by sharp divisions both personally and philosophically. Vinson was known as a conciliator, someone who could get people with differing ideas to work together.

Besides attempting to be a conciliator on the Court between the two warring factions and between two justices who had strong personalities and a strong dislike for each other, Vinson brought a distinct judicial philosophy to the role of chief justice. Having been a member of Congress, Vinson recognized and respected the principle of legislative intent that lay behind the laws in the cases brought before the Court. He leaned toward judicial restraint, believing that the remedy for any laws that needed to be changed lay with the ballot box. Vinson wanted to find the law in the cases that the Court considered, not make the law.

The Vinson Court dealt with important issues in postwar America: cases involving the United Mine Workers and the steel industry, cases that involved finding the balance between free speech and the threat of Communist influence, and most significantly cases that addressed segregation and inequality in housing and in graduate education at a time of great ferment regarding relations between black persons and white persons in America.

A common practice in home buying was for buyers and sellers to sign what were called restrictive covenants. These covenants forbade the sale of homes to certain individuals, most notably black persons. The Court ruled against the practice of restrictive covenants in the selling of homes.

Regarding education, the state of Oklahoma had a practice of paying the tuition for black students to attend law school out of the state rather than have black students attend law school with white students. Later Oklahoma established an obviously unequal facility for black law students in-state. In another case involving graduate studies in Oklahoma, a university admitted a black student but required him to sit in an alcove in the classroom to keep him separate from white students. In another case, Texas had also created a separate but obviously unequal law school for black students.

In all of these cases, the Vinson Court found that these practices denied black students equal protection of the law, which violated the 14th Amendment. The Court moved carefully in these cases. It did not strike down segregation in general, but only did so specifically in the situations involved in the cases. But the Vinson Court’s decisions did set the stage for the Brown v. Board of Education decision, which the Court handed down in 1954, the year after Vinson died.

1953 saw a new president, Dwight Eisenhower, inaugurated into office. Fred Vinson administered the oath of office, just as he had done four years earlier when Harry Truman was inaugurated for a full term after winning the 1948 presidential election.

Vinson occasionally played bridge with Eisenhower at the White House. In August of 1953 Vinson rejoiced at the birth of his first grandchild. Then Vinson died suddenly of a massive heart attack on September 8, 1953, at the age of 63.

Chief Justice Fred Vinson was entitled to lie in state in the Capitol rotunda in Washington, but his family chose rather to have his casket placed in a simple Washington funeral home for the lying in state, where hundreds of people came to pay their last respects. In attendance at the funeral held at the Washington Cathedral were President Dwight Eisenhower, former president Harry Truman, and of course many other friends and colleagues. The next day a service was conducted at Vinson’s church in his home town of Louisa, attended by Vinson’s fellow Supreme Court justices, Kentucky’s governor and two senators, the speaker of the House of Representatives, and Alben Barkley, a former vice president and former senator from Kentucky. These and others filled the 300 seats inside, and hundreds more listened on loudspeakers outside. A congressman from Kentucky described the service in a letter:

“I have never seen a tribute more genuine or more American than that demonstrated by his friends in Kentucky and elsewhere who gathered for the final rites. . . .” Besides the famous and powerful people in attendance, the congressman said, were “farmers, laborers, and plain citizens, men in overalls and working clothes, but all with the same thought and objective–to pay tribute to a great man.”

My interest in Fred Vinson began during my first semester in graduate studies in history at the University of Kentucky. During that semester, Vinson’s official papers were donated to the library at the University, and I was one of the first students to examine those papers. I wrote a few term papers using those materials. It was a thrill to me to be able to read documents marked Top Secret and Confidential and to handle letters and memos personally signed by Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman.

I hope this podcast will help you appreciate the role Fred Vinson played in the American story during his 30 years of public service. He played a critical role in helping to oversee and guide the American economy during and after World War II. He led the Supreme Court in confronting major issues that faced the country in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He was one of only a handful of people in American history to serve in all three branches of the federal government: legislative, executive, and judicial.

You might not expect a young man from a small town in the Appalachian Mountains of Eastern Kentucky to hold some of the highest positions in the national government. But Fred Vinson did. He wanted to serve his country. He worked at it. He didn’t give up. That’s a lesson for you or your child in how to be a citizen who makes a difference.

Notgrass History curriculum teaches students about U.S. government. In the civics curriculum Uncle Sam and You for middle school, we help students understand how government works on the local, state, and national levels and how students can be involved in making their communities better places. In Exploring Government for high school, we give students an extensive understanding of the U.S. Constitution, the workings of government on the local, state, and federal levels, and the issues that confront our government today. We teach that government is from God and that serving in government and in our communities is a stewardship from God that citizens must fulfill.

Two years before his death, Fred Vinson attended the dedication of a monument erected on the town square in Louisa, Kentucky, to honor his birthplace. On that occasion Vinson said, “From where I stand, I see my birthplace. I see my school and its playground, where my education began. Over there is the temple of justice (meaning the courthouse) where my career in law began. And there is the temple of my faith,” meaning his church.

The minister who presided at the funeral later recalled, “The graveside service was simple with hundreds of people there paying tribute to one they loved, to a local boy buried in judicial robe and one who started there sixty-three years ago and who had reached the highest pinnacle in his profession, but still a local boy. To me,” the minister said, “this was and is America.”

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thank you for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History for more information about Fred Vinson and the Supreme Court, including specific cases he was involved with as Chief Justice.