Ray Notgrass: On today’s Exploring History podcast, we’ll tell the true dramatic story of a time when God dealt a hand made up of a king, two queens, a knave, and an ace.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

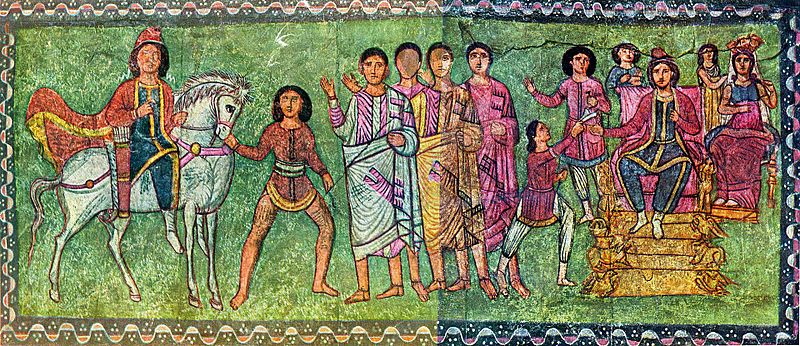

Ray Notgrass: God places a beautiful young woman in a position of influence. She risks her own life to save her entire people group from merciless execution. The villain behind the cruel plan is shown to be the king’s highest-ranking advisor. When the young woman exposes the villain and he is executed, he is replaced by his nemesis, who is the kindly man that had reared the young woman after she had been orphaned.

The story of Esther is an account of selfless courage and of good triumphing over evil, but above all it is a demonstration of God’s guiding hand of providence. It tells of Esther’s brave action that prevented the murder of all the Jews in the huge Persian Empire. This deliverance of the Jews is the basis for the feast of Purim, which Jews celebrate every year to this day.

The story of Esther is told in the Old Testament book of that name. The Bible is a book of faith, but it is also a book of history. We do both the Bible and history an injustice when we treat them as separate. We learn a lot of history from the Bible. The account of Esther is one example.

The setting of this story is the ancient Persian Empire. Cyrus, the king of Persia, conquered Babylon in 539 BC. Babylon had conquered Judah about 60 years earlier and had taken thousands of Jews into captivity in Babylon. The year after Cyrus defeated Babylon, he issued a decree that allowed the Jews to return to their homeland in Israel. Many of them did so, but a significant number of Jews decided to continue living where they were. Darius was king of Persia a few years after Cyrus. The son of Darius was Ahasuerus, who ruled Persia from 485 to 465 BC. Ahasuerus is the Hebrew transliteration of his Persian name. The Greek form of his name is Xerxes. It is this Ahasuerus or Xerxes that is the king in this story. The events take place in the Persian capital city of Susa, also called Shushan, in 478 BC.

The book of Esther opens with an account of the king in the hand God dealt, Ahasuerus, putting on a great banquet for his officials and servants. The banquet lasted for many days. Meanwhile Vashti, his queen, who is one queen in the story, hosted a separate banquet for women.

On the seventh day of the feast, the king, whose heart was merry with wine, ordered Vashti to come before his guests so that they could admire her beauty. Vashti refused. Scripture does not state the reason for her refusal. She might have been insulted by the king’s intoxication, or perhaps she did not want to be made a public spectacle.

The embarrassed and infuriated Ahasuerus consulted his wise men on what to do. This was a common practice of eastern potentates. The wise men advised the king that he should remove Vashti as queen and choose another to take her place. They warned the king that Vashti’s refusal would be a bad example to other women in the Persian empire. The decision that Ahasuerus made would become part of the law of the Medes and the Persians, which could not be changed because Persian pride would suffer if someone suggested that their laws could be improved.

The banquet of chapter 1 occurred in the third year of the reign of Ahasuerus, and the selection of a new queen took place in the seventh year. The king ordered that his agents go throughout the kingdom and gather attractive, unmarried young women for the king to consider as his new queen.

The story now focuses on one of these women, Hadassah or Esther, and her adoptive father, Mordecai. Mordecai was of the tribe of Benjamin and lived in the capital city of Susa. The name Mordecai is the Hebrew form of the Babylonian name Mardukaya, which refers to Marduk, chief god of the Babylonians. The Persians adopted the worship of Marduk when they conquered Babylon. Mordecai was obviously a faithful Jew, but his name suggests that his family had adapted to Persian culture to some degree.

Esther 2:5 lists Mordecai’s ancestors. These references to his ancestors are significant. One important fact about a person in Jewish eyes was the identity of his father and his ancestors. This is why the Bible has several such references and genealogies. Who a person’s father was said something about that person. Mentioning a person’s forbears also gave that person a reputation to live up to. The importance of family responsibility and family reputation is a lesson from which we could profit today.

Mordecai had reared his first cousin, Hadassah, after her parents died, so he must have been a good bit older than she. “Hadassah,” means “myrtle” in Hebrew. Her Greek name Esther was apparently Persian for “star,” though some have connected the name to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. Many Jews have had and continue today to have a Hebrew name as well as a name from the surrounding culture, such as Daniel, who was also called Belteshazzar and the apostle Saul, known as Paul.

Esther’s beauty qualified her to be one of the candidates for queen. Esther received special treatment during her time of preparation to meet with the king, which indicates that the hand of the Lord was with her. Esther did not reveal her identity as a Jew because Mordecai advised her not to. Mordecai understandably feared that a Jewish woman might not be accepted as queen of Persia. Esther was of foreign ancestry and was the descendant of people who were formerly captives. In addition, anti-Jewish feeling was strong throughout the ancient world. Anti-Semistism is nothing new. The fact that Esther did not disclose her Jewish ancestry at this point sets the stage for when she does reveal it dramatically later in the story.

When Esther’s turn came for the king to consider her, she found favor with all who saw her. This was another indication of God’s providence. King Ahasuerus delighted in Esther more than all the other women. The narrator tells us that Esther “found favor and kindness with him.” And so the king chose Esther to be his new queen. This made her the second queen in the story.

Following Esther’s selection, an incident took place that foreshadows a coming event. Mordecai learned of an assassination plot against King Ahasuerus by two of his doorkeepers. Mordecai told Esther, and Esther informed the king. An investigation confirmed Mordecai’s accusation. The conspirators were hanged and a royal scribe recorded Mordecai’s act of service in the book of the chronicles of the king.

King Ahasuerus promoted a man named Haman to the position we would call grand vizier and ordered all of his servants to pay homage to Haman. Mordecai, however, did not bow before Haman. No doubt Mordecai knew the character of Haman, who is the knave in this story, and refused to give honor to a dishonorable man. Although the new grand vizier had all the wealth and power he could ever want, he lacked one thing: subservience from Mordecai; and this infuriated Haman. Perhaps out of an overpowering desire for revenge, and perhaps because he knew that if one Jew refused to honor him all Jews would do the same, Haman resolved to wipe out the Jewish people in the Persian Empire. We today might find his scheme incredible if we did not know of repeated anti-Jewish campaigns throughout history and especially the attempt to destroy the Jews of Europe by Nazi Germany. Our world still has violent groups who want to kill Jewish people, as evidenced by the October 7, 2023, attacks on Israel.

The date for carrying out Hama’s murderous plan was determined by the casting of lots. Lots could be sticks, stones, pig knuckles, or other objects marked in a certain way and cast or dropped to determine the answer to a question. The lots were cast in the month of Nisan, the month in which Jews observe Passover. This is significant because Passover commemorates God’s deliverance of Israel from an earlier threat. The ethnic cleansing that Haman hoped to accomplish was to be carried out eleven months later. After the decree was written, translated, and distributed throughout the empire with the king’s approval, the king and his cold-blooded grand vizier sat down calmly to have a drink.

When Mordecai heard about this decree that endangered his people, he went into mourning, as did all the Jews. When Esther learned the reason for Mordecai’s grief, her first reaction was to explain why she was powerless to do anything to stop the decree. If she approached the king uninvited, she risked being put to death.

Mordecai, the ace in the hand that God dealt, reminded her that she was a condemned woman either way, whether the king rejected her when she came to talk to him or she did nothing. She had nothing to lose, so her only hope was to go to the king. Mordecai believed that God would rescue His people. Help for the Jews would come from somewhere, Mordecai stated, and then he said, “and who knows whether you have not attained royalty for such a time as this?” (Esther 4:14). God would deliver His people, Mordecai said, and Esther just might be His chosen instrument to bring this about. Esther resolved to go to the king, and she asked the Jews to devote three days to fasting (and we assume prayer) before she went.

The king’s love for Esther led him to receive her and to offer her anything she wanted, up to half the kingdom. Her first request was for the king and Haman to attend a banquet that day. At the banquet, she requested that they return for another banquet the next day. She might have taken these cautious steps to see how receptive the king was and to snare the egotistical Haman in his own trap.

Haman left the first banquet full of pride; but when Mordecai once more refused to bow to him, his bubble burst. The grand vizier poured out his frustrations to his wife and friends, who suggested that Haman have Mordecai executed as an example to other Jews and as a way to satisfy Haman’s cruel desire for revenge. Haman ordered that a custom gallows be constructed immediately.

That night the sleepless king asked for his official records to be read to him. Perhaps this was to build up his pride or maybe it was a sure way to be put to sleep. This reading reminded King Ahasuerus of the time that Mordecai intervened and thus saved the king’s life; and he also learned that nothing had ever been done to honor Mordecai for his help. No doubt it was providential that the king heard this portion of his record that night. Just then Haman entered the palace to request that Mordecai be executed. Before Haman could make his request, the king asked him what he thought should be done for the person whom the king wished to honor. Haman, assuming that the person in question was himself, pulled out all the stops in describing a lavish ceremony. The king agreed and ordered Haman to honor Mordecai in just this way. Haman was mortified by having to do so, and the irony of this turn of events also was probably not lost on the citizens of Susa.

Haman arrived at the second banquet a discouraged and embittered man. In his mind, he had been at the top but now he could hardly imagine being lower. Finally Esther made her request of the king; her request was for her very life and the lives of her people. She said that they had been sold in order to be destroyed. She was referring to Haman’s offer, described in Esther 3:9, to pay ten thousand talents to those who carried out the slaughter of the Jews. If her people had only been sold into slavery, Esther continued, she would not have said anything; but this threat prompted her request for the king’s help.

King Ahasuerus was shocked and demanded to know who would do this. Esther identified the culprit as Haman, the other guest at her table, who had fallen into the trap that he had set for himself by his own pride. Now the king saw the grand vizier for what he was. Furious, the king stormed out of the banquet to think things over. Haman, meanwhile, knew that he was a dead man and began pleading with Esther to intervene on his behalf. His entreaties were so desperate that he fell across the couch where Esther was reclining for the banquet. At this point the king returned and saw what looked like Haman attempting to assault the queen.

At the word of the king, the courtiers covered Haman’s face in preparation for his execution. He was put to death at the very time and on the very gallows where he had hoped to put Mordecai to death.

King Ahasuerus gave Esther the house of Haman, since the property of condemned criminals reverted to the state. Esther in turn appointed Mordecai to be in charge of this property, which apparently was of considerable worth.

Of even greater significance was the fact that the king gave Mordecai his signet ring, the same one that Haman had used to authorize the edict he had issued against the Jews. This meant that Mordecai was now grand vizier, with all of the power and prestige that Haman had once enjoyed and that he had abused in that role.

But Haman’s decree calling for the annihilation of the Jews remained on the books because the law of the Medes and the Persians could not be changed. At the request of Esther and Mordecai, the king authorized them to write a new decree that would help defend their people. He told the new grand vizier to sign it with the king’s name and seal it with the royal seal. No more authoritative law existed in the empire.

The new edict allowed the Jews to gather together for the purpose of defending themselves. The wording of Mordecai’s decree was almost exactly the same as what Haman’s edict had called for, except now it applied to the enemies of the Jews. Now the Jews were on equal footing with their enemies. The day when the Jews could carry this out was the thirteenth of Adar, the same day on which Haman’s law had called for the Jews to be attacked. Copies of the law were distributed in Susa and in all of the provinces. It was translated into the various languages that were used in the empire, including the language of the Jews.

The book of Esther indicates that many people in the Persian Empire converted to Judaism. The implication from the text is that people recognized the power of God through what had taken place and were convinced that God was indeed worthy of being worshiped. The events that had unfolded involving Esther, Haman, and Mordecai, told the people not that the Jews were merely lucky or that they had somehow manipulated things to gain the upper hand, but that the God of the Jews was truly Lord over all the earth.

Finally the day arrived, the thirteenth of Adar, when the Jews had been marked out for annihilation. The proposed slaughter became a showdown, and it resulted in one of the greatest victories in the history of Israel. God’s covenant people were triumphant over wicked forces. This victory came about because one man, Mordecai, refused to believe that God would abandon His people and because one woman, Esther, risked her life to save her people.

Provincial officials used their influence to help the Jews because the officials feared the power of Mordecai. They knew how Mordecai had come into his position. They knew that the fortunes of Haman and Mordecai had been dramatically reversed. The provincial officials might not have fully understood the Divine Power behind Mordecai’s rise to prominence, but they knew something or Someone was there. Mordecai’s reputation grew, and he was recognized as a man to be reckoned with.

The capital city saw its own demonstration of the Jews’ power. In the citadel of Susa, the Jews killed five hundred people who dared to follow Haman’s edict and attack God’s chosen people. The book of Esther identifies ten of the victims for us: the ten sons of Haman. Haman’s wife was again forced into mourning because of her husband’s sins. In the Hebrew text of Esther, the names of these ten sons of Haman are written perpendicularly, down the page, to call attention to them. The Jews did not plunder the possessions of their foes. The action that the Jews took was not about gaining wealth but about saving their lives.

King Ahasuerus learned of the casualties in the citadel of Susa. He then relayed the information to Esther and implied that if this was the toll in the capital, it must have been much greater in the provinces. It was a time of great satisfaction for the royal couple and for the Jews. The king noted that his granting of Esther’s request had brought about this victory for her people. Continuing his gracious indulgence of his queen, he wondered what her next request might be.

Esther’s desire was to exact more vengeance. She wanted the Jews in Susa to have another day in which they could attack and destroy all who threatened them. The queen also asked that the bodies of the ten sons of Haman be hanged from the gallows, probably the same gallows where their father had been executed. The king ordered it done. This sounds cruel, but in ancient times this was common practice with notorious criminals.

After their fierce battles, the Jews who lived in the provinces rested and celebrated on the fourteenth of Adar. In Susa, the Jews defended themselves for two days (the thirteenth and fourteenth of the month), and then rested and celebrated on the fifteenth. What had been intended to be a day of death for the Jews turned out to be a day of triumph for them.

The Jews who lived in the provinces of the Persian Empire celebrated on the basis of the timing of their experience. They had successfully defended themselves on the thirteenth of Adar, so they made the fourteenth a day of feasting and gladness and exchanged gifts with one another. In a similar way, the Jews who lived in the citadel of Susa celebrated on the basis of their experience. They had defended themselves for two days, the thirteenth and fourteenth, and so they celebrated on the fifteenth.

Mordecai issued a decree to settle the question of when the Jews should celebrate their deliverance. He instructed the Jews to observe a two-day festival that commemorated both days of deliverance, the fourteenth and the fifteenth. The festival reminded the Jews of the time when their sorrow had turned to joy. They made the feast a time of great rejoicing; and they remembered others as God had remembered them, by exchanging presents and giving gifts to the poor.

The feast of Purim occurs about a month before Passover in the last month of the Jewish festival year. It is held between late February and late March on our calendar, depending on how the Jewish lunar calendar coordinates with it. This year, 2024, the feast of Purim falls on March 23 and 24.

The Jews called the festival Purim, the Hebrew plural form of pur or lot, because the Jews were saved on the day that the pur had indicated they should die. Because of what had happened and because of Mordecai’s letter regarding the observance of the feast, the Jews bound themselves and their descendants to observe Purim annually on the fourteenth and fifteenth of Adar. The Jews wanted it to be a universal observance. They did not want later generations to forget the experience that had saved their lives and shown them the hand of God.

Esther sent out a letter giving her royal endorsement of Mordecai’s proclamation. Mordecai’s letter to the provincial leaders, the narrative says, contained “words of peace and truth.” This was the typical greeting of oriental letters of the day, and it is a worthy

standard for our words today. The grand vizier’s letter confirmed his earlier decree about the observance of Purim and discussed “their times of fasting and lamenting.” This probably had to do with a fast that the Jews held just prior to Purim, recalling the danger they had faced from their enemies. Jews still observe this fast, and it is called the Fast of Esther.

The final brief chapter of the book of Esther mentions one additional fact about Ahasuerus and summarizes Mordecai’s tenure as grand vizier. Mordecai carried out his duties well as one who “sought the good of his people and . . . spoke for the welfare of his whole nation” (Esther 10:3).

Consider the situation of the Jewish people in the Persian Empire. They were strangers in a strange land. They spoke a different language, had different customs, and even used a different calendar from the majority of the people who lived there. The most striking difference about them, however, was that they worshiped a different God. The wrath of the government was called down upon them because one Jew decided not to bow down to an evil adviser to the king. When the Jews faced extinction, the courage of one Jewish woman spared them. They had a reason to celebrate and to give thanks that God had not abandoned them in that foreign land.

Today the feast of Purim is a joyous celebration. The book of Esther is read in a chant. Those assembled cheer and boo at appropriate times, and people often dress in costume to represent characters from the story. They recite blessings, sing hymns of praise, and enjoy a festive meal. In every way it is an atmosphere of celebration. Later generations were never to forget that the hand of God had saved them.

Because of the popularity of the book of Esther with the Jewish people over the centuries, more manuscript copies of Esther exist than of any other Old Testament book. It also received extensive treatment by the rabbis in commentaries on Scripture that were compiled around the first century AD. Esther is unusual for a book in the Bible in that it does not mention the name of God; however, God’s providence is obvious, and the reference to fasting implies prayer. God is the main character of the story.

The book of Esther is a gripping drama, and all the more so because it is true. It is a thrilling testimony to God’s sovereign and powerful hand working on behalf of His people. As we consider the story, enjoy the narrative, and rejoice in the outcome, we should also rejoice at God’s providential mercy that rules our lives today and remember how we have been called to live for Him in such a time as this. May we also never forget.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History for more resources related to the story of Esther and the holiday of Purim.