Ray Notgrass: It happened 50 years ago this month. It hadn’t happened before, and it hasn’t happened again since.

Titus Anderson: [music in background] Welcome to Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History.

Ray Notgrass: I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Before we get into the subject of today’s podcast, Charlene and I would like to thank the many people who have offered prayers and words of encouragement following the passing of our daughter Bethany on July 30, 2024. She was a beautiful person who blessed others and who shone the light of Christ wherever she went. We will miss her every day until we are reunited with her in heaven. Thank you.

Fifty years ago, on August 9, 1974, Richard Nixon resigned the office of president of the United States. It was a tragic fall from the heights of political power, and on today’s podcast we’ll examine how the Nixon presidency unraveled. At various points I’ll add in my personal remembrances of that time. I was in college and very interested in politics. I remember many of those events and reactions of the public very clearly.

Richard Milhous Nixon was born in 1912 to Quaker parents, a lemon farmer and his wife in Yorba Linda, California. He went to Duke University Law School, quite an accomplishment for a poor boy from California, and then enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War II. After the war, he won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1946, was reelected in 1948, and won a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1950.

A hot issue in the country at the time was the fear of Communist infiltration in government, and Nixon pursued that issue actively. Nixon was very involved in the Alger Hiss case, which we will have to discuss at another time. Then in 1952, Dwight Eisenhower selected Nixon to be his vice presidential running mate in that year’s presidential election. However, during the campaign, questions arose about a special fund that contributors created for Nixon to use for various expenses. Many wondered if Nixon should resign from the Republican ticket because of the questions and potential scandal. But Nixon made a televised speech in which he defended the fund, denied any wrongdoing, and appealed to viewers to make their opinions known to the Republican National Committee. The response in support of Nixon was overwhelming, and Eisenhower kept him as his running mate. This was the first of several times in Nixon’s career that he made a comeback from political difficulties. The speech Nixon made is often called the “Checkers” speech, because in it, Nixon made reference to a dog named Checkers that someone had given his daughters. He said that, whatever happened, his family was going to keep Checkers.

Nixon was Eisenhower’s vice president for eight years and was active in the administration, especially in the area of foreign policy. Nixon ran for president himself in 1960, but Senator John Kennedy defeated him in a close contest. Nixon tried to make a comeback by running for governor of California in 1962. Pretty much everyone knew that Nixon wasn’t interested in being governor of California, but he was using the contest to restart his national political ambitions. However, Nixon lost that race also. The day after the election, at a press conference, a tired and bitter Nixon said farewell to the reporters present. It appeared that he was leaving politics when he added, “You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

Nixon went back to practicing law and to making speeches to Republican groups around the country as the former vice president. Over the next few years, Nixon made another comeback. He rebuilt his reputation and his status as a Republican leader. In 1968 Nixon won the Republican nomination for president. He defeated then-vice president Hubert Humphrey in a very close race and became president. Republicans never held a majority in either the House or the Senate during Nixon’s presidency, so Nixon had a tough time getting many of his proposals enacted into law. He was able to reduce significantly American involvement in Vietnam; but at home, inflation was a constant problem during his time in office.

As Nixon’s 1972 reelection effort was getting underway, he accomplished diplomatic breakthroughs by visiting both the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union in the first part of 1972. It turned out that President Nixon was a formidable candidate for reelection. The campaign organization, called the Committee to Re-Elect the President, brought in a record amount of contributions to finance the campaign.

Meanwhile, the Democrats were badly divided. They were united in opposing Nixon, but the liberal, moderate, and conservative segments of the party distrusted each other. Alabama governor George Wallace ran for president again as he had in 1968, but this time he pursued the Democratic nomination rather than running as an independent. Wallace made impressive showings in early primaries outside of the South. However, while campaigning in Laurel, Maryland, on May 15, 1972, a mentally unbalanced man named Arthur Bremer shot and wounded Wallace. As a result of the shooting, Wallace was paralyzed from the waist down. Wallace won the Maryland and Michigan primaries the next day, but his disabling injury forced him to end his campaign.

South Dakota senator George McGovern led the liberal wing of the Democratic Party. McGovern was a World War II bomber pilot who had received the Distinguished Flying Cross. McGovern earned a Ph.D. in history and taught at Dakota Wesleyan University, his alma mater. McGovern had represented South Dakota in the U.S. House of Representatives and then in the U.S. Senate. McGovern had worked within the Democratic Party to help more black persons, women, and young adults to participate in the political process and especially the national convention; but these changes alienated the old-time Democratic political bosses.

McGovern strongly opposed the Vietnam War. He received the Democratic nomination and named Missouri senator Thomas Eagleton as his running mate. However, the Democrats seemed bent on political self-destruction. Not only did the Democrats nominate the liberal McGovern, but the final convention session ran late and McGovern’s acceptance speech was delayed until well after midnight.

Then a few days after the convention, the news broke that Senator Eagleton had received psychiatric electric shock treatments in the 1960s. Many Democrats believed that Eagleton should resign from the ticket, but McGovern said that he supported his running mate “one thousand percent.” However, the pressure for Eagleton to withdraw continued to increase; and he eventually stepped down for what he called the good of the party. The Democrats replaced Eagleton with Sargent Shriver, who was married to John Kennedy’s sister and who had been director of the Peace Corps.

Thus the Democrats were divided and in disarray, while the incumbent Nixon had a smooth-running and well-financed campaign. McGovern was perceived as being so far out of the mainstream that even the typically Democratic AFL-CIO labor organization endorsed the Republican Nixon instead of the Democrat McGovern.

So in mid-1972, it looked like Nixon was on his way to a huge victory and another four years in the White House. But a tiny cloud appeared on the horizon. Early on the morning of June 17, 1972, five burglars were arrested at the offices of the Democratic National Committee in the office and apartment complex in Washington, D.C., known as the Watergate. The men arrested, along with their supervisors, Gordon Liddy and Howard Hunt, were employed by the Committee to Re-Elect the President. The men had electronic surveillance equipment on them and were apparently bugging or re-bugging the Democratic offices. It turned out that the men had broken into the DNC offices a few weeks before and were trying to correct the work that they had done then.

At the time this happened, I was in college and working weekends at a local radio station. I remember hearing a story on a radio network newscast on that Sunday about the break-in. I remember thinking, “Hmm. That’s interesting. I wonder what that’s about,” but I didn’t give it much more thought than that.

Not much came of the incident during the campaign, and both the White House and the reelection committee denied any knowledge of or involvement in the burglary. One poll during the campaign indicated that 48% of the public had not even heard of the Watergate incident. The men directly involved in the break-in pleaded guilty and eventually went to jail.

In November of 1972 Nixon won in the biggest Republican landslide to that time: 47.2 million (or 61%) for Nixon to 29.2 million (38%) for McGovern in popular votes and a whopping 520 to 17 victory in the electoral count. McGovern only carried the state of Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. However, the Democrats still had majorities in both houses of Congress.

Nixon was inaugurated for a second term in January of 1973. However, the Washington Post newspaper continued to investigate the Watergate burglary. Reporters found a trail of evidence connecting the burglars to both the White House and the Nixon campaign. A special Senate committee also looked into the matter and found additional evidence of wrongdoing at high levels in the Nixon administration. Aides close to President Nixon resigned in April of 1973 as charges of criminal activity and illegal cover-ups increased.

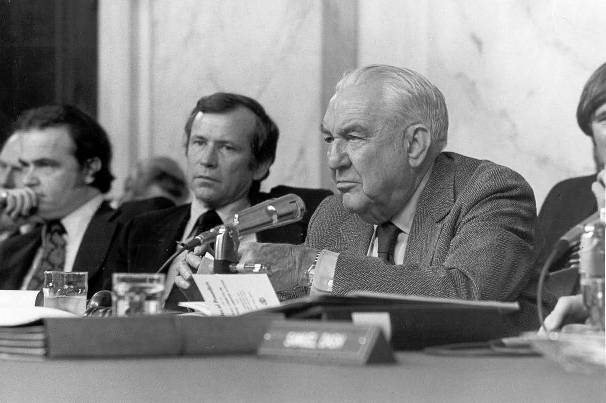

The counselor to the president, John Dean, testified in June 1973 before the special Senate investigating committee that the president, his top aides, and the Justice Department had conspired to conceal evidence connected to the Watergate incident and other illegal campaign activity. North Carolina Democratic senator Sam Ervin chaired the Senate investigating committee hearings and tolerated no compromise with the truth. The highest ranking Republican member of the committee, Senator Howard Baker of Tennessee, repeatedly asked witnesses, “What did the president know and when did he know it?” This turned out to be the crucial question regarding the president’s involvement.

From mid-1973 until August 1974, Watergate was the top political story in the country every day. Every major headline screamed it, and every nightly newscast began with the latest reports surrounding the scandal. And these reports weren’t only about the Watergate break-in. Reports surfaced of other illegal activities by members of Nixon’s administration to find out information or to plant misinformation about people Nixon perceived as his political enemies. Watergate turned out to be not an isolated incident, but only one of a long series of behind-the-scenes activities designed to destroy Nixon’s critics and political opponents. I remember deciding that I was going to follow this story closely to figure it all out, but the rapidly increasing number of stories and the spread of issues soon became such that it was impossible for me to do that.

Nixon consistently maintained his innocence and said that he wanted all wrongdoers brought to justice. For instance, in a November 1973 televised question-and-answer session with Associated Press editors, Nixon said, “I welcome this kind of examination because people have got to know if their president is a crook. Well, I'm not a crook.” Against his wishes but because of increasing public and political pressure, Nixon appointed a special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, in May of 1973 to look into the growing scandal. A federal grand jury under Judge John Sirica worked with Cox. So at this point, a special prosecutor was trying to find out what happened, the Senate's investigating committee was trying to find out what happened, and so were reporters of the Washington Post and other news sources. Watergate truly consumed the political energy of Washington and the entire country.

On July 13, 1973, a White House aide, Alexander Butterfield, revealed in his testimony before the Senate committee that Nixon had installed a secret taping system in the Oval Office to record conversations and phone calls. Special prosecutor Cox obtained a court order to gain access to the tapes; but Nixon refused to hand them over, citing executive privilege to keep the tapes from being made public. Cox continued trying to obtain the tapes, so Nixon ordered Cox fired on Saturday, October 20, 1973. Attorney General Elliott Richardson refused to fire Cox and instead resigned. The deputy attorney general, William Ruckelshaus, also refused to fire Cox, so Nixon fired Ruckelshaus. The solicitor general, Robert Bork, was next in line in the Justice Department; and he agreed to fire Cox. The incident became known as the Saturday Night Massacre. A new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski, continued to seek access to the tapes. Judge Sirica ordered that they be turned over, but Nixon continued to refuse.

Although things couldn’t seem to get worse for the Republicans, they did. As the result of a separate investigation, Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned on October 10, 1973, and pleaded no contest to a charge of tax evasion related to bribes he had received from contractors while he was governor of Maryland. Nixon appointed and Congress confirmed Gerald Ford as the first nonelected vice president chosen under the provisions of the 25th Amendment.

President Nixon stated in a national broadcast on April 29, 1974, that he was disclosing to the public edited transcripts of the White House tapes in question. The president hoped that these transcripts would show his innocence. One tape that he made public had a gap of silence that lasted about 18 1/2 minutes. The gap had apparently occurred when someone erased part of the tape. The president’s secretary said that she might have accidentally erased the tape while transcribing its contents, but many people believed that someone intentionally erased that segment of the tape.

In May of 1974, the Judiciary Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives, after conducting its own investigation, began formal hearings to determine whether Nixon should be impeached for high crimes and misdemeanors and have to face a trial in the Senate, possibly leading to his removal from office.

In July of 1974, the Supreme Court ruled in a unanimous decision that Nixon had to release the tapes to the special prosecutor. Also that month, the House Judiciary Committee passed and sent to the full House three articles of impeachment against President Nixon. The charges claimed that Nixon was guilty of obstruction of justice by helping to cover up evidence related to the Watergate investigation, that he refused to cooperate with the Judiciary Committee, and that he was guilty of abuse of power in misusing government agencies to obtain information about private citizens.

Nixon then released transcripts of tape-recorded conversations made just a few days after the Watergate break-in. These transcripts showed that, although Nixon did not participate in planning the Watergate burglary, he did help conceal evidence and he agreed to mislead the public about his involvement and the involvement of others in his administration. The transcripts were the “smoking gun” evidence that showed the president to be guilty of covering up evidence of a crime..

As the evidence became clear, fewer and fewer Republicans in Congress were willing to defend Nixon. More and more of them indicated that they would vote for impeachment and conviction. Faced with the Democrat-controlled House about to vote on the articles of impeachment and the Democrat-controlled Senate then bound to hold an impeachment trial, President Nixon resigned effective at noon on August 9, 1974. He left Washington shortly before noon and became a private citizen while flying back to California. Vice President Gerald Ford was sworn in at noon on August 9 as president. Ford was the first person to hold the offices of vice president and president whom the voters of the country had not elected to either office.

I kept asking, “Can this be happening? How could someone who had won in a landslide resign less than two years later? Why in the world would Nixon and his aides stoop to such trickery and deceit when his election was all but certain?”

So in August of 1974, Nixon was out of office and the country began to focus on other matters. One such matter was the off-year congressional election that fall, in which Republicans lost badly. But one month after taking office, on Sunday morning, September 8, 1974, President Ford went on national television to issue a full, free, and absolute pardon to Richard Nixon for any federal crimes he might have committed while president. Many people suspected that Nixon, before he resigned, had made a deal with Ford to do this, but Ford always denied making any such deal. The new president said that he wanted to move on from Watergate and that putting a former president on trial would not help the country. It was time, Ford said, for the healing and recovery to begin. Some election observers wondered if Ford’s pardon of Nixon cost him the close election of 1976 when he ran against Jimmy Carter. Since then, most historians and political observers have agreed that Ford made the right decision for the country, however much it cost him politically.

Amazingly, in retirement Nixon engineered something of another comeback to respectability. The former president admitted in a 1977 television interview with David Frost that he made mistakes regarding Watergate. Nixon authored several books, mostly on foreign policy, and visited foreign leaders as a private citizen.

Pat Nixon, the wife of the former president, died in 1993. Her funeral was televised. The image of the grieving former president who resigned in disgrace weeping at the death of the woman who had stood by him throughout his career was truly sad.

I think of Richard Nixon as an almost great president. He was intelligent and capable. He did many things right. But his personal weaknesses brought him down. Nixon was on the national Republican ticket five times: twice as a candidate for vice president and three times as a candidate for president. He was on the winning ticket four of those five elections, and yet he never deeply believed that the American people trusted and supported him. According to reliable reports, on the evening of his greatest victory, the 1972 landslide, Nixon was gathered with his closest advisers not in an attitude of joy but in a spirit of anger and revenge. “Now we’re going to show them,” was the attitude he expressed toward his political opponents. “Now we’re going to take charge and clean house.” How sad that he could not enjoy his greatest victory in his last election campaign but instead gave in to bitterness and resentment.

Richard Nixon died in 1994, ending a public life that spanned almost 50 years. One of the speakers at the funeral was then president Bill Clinton, a Democrat. Nixon and Clinton had held a few telephone conversations during Clinton’s time in office, during which Nixon provided Clinton with advice about foreign policy. During his remarks at Nixon’s funeral, Clinton said, “The enduring lesson of Richard Nixon is that he never gave up being part of the action and passion of his times. He said many times that unless a person has a goal, a new mountain to climb, his spirit will die. Well, based on our last phone conversation and the letter he wrote me just a month ago, I can say that his spirit was very much alive to the very end. That is a great tribute to him, to his wonderful wife, Pat, to his children, and to his grandchildren whose love he so depended on and whose love he returned in full measure.”

Clinton went on to say, “Today is a day for his family, his friends, and his nation to remember President Nixon's life in totality. To them, let us say, may the day of judging President Nixon on anything less than his entire life and career come to a close.” Those were just and generous words.

I’m Ray Notgrass. Thanks for listening.

Titus Anderson: This has been Exploring History with Ray Notgrass, a production of Notgrass History. Be sure to subscribe to the podcast in your favorite podcast app. And please leave a rating and review so that we can reach more people with our episodes. If you want to learn about new homeschool resources and opportunities from Notgrass History, you can sign up for our email newsletter at ExploringHistoryPodcast.com. This program was produced by me, Titus Anderson. Thanks for listening!

Visit Homeschool History for links to more photos and information about Richard Nixon and Watergate.